In the 1950s and ’60s, track and field athletes could become models on Wheaties boxes, stars on television and objects of fascination to the news media. There were Bob Richards, an ordained minister and pole-vaulter nicknamed the Vaulting Vicar, and Dick Fosbury, a high jumper whose distinctive leap became renowned as the Fosbury Flop.

Richards and Fosbury died in February and March, occasioning a final round of news coverage about their careers. Yet John Uelses, a pole-vaulting peer of theirs who attained the era’s classic feat of athletic celebrity, appearing on the cover of Sports Illustrated, died seven months ago in San Diego without the public taking much notice.

His death, at 85, on Dec. 15 last year, was caused by complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said his daughter, Elyssa Robertson. Apparently the only news of his death was an announcement the family posted early this year on Legacy.com.

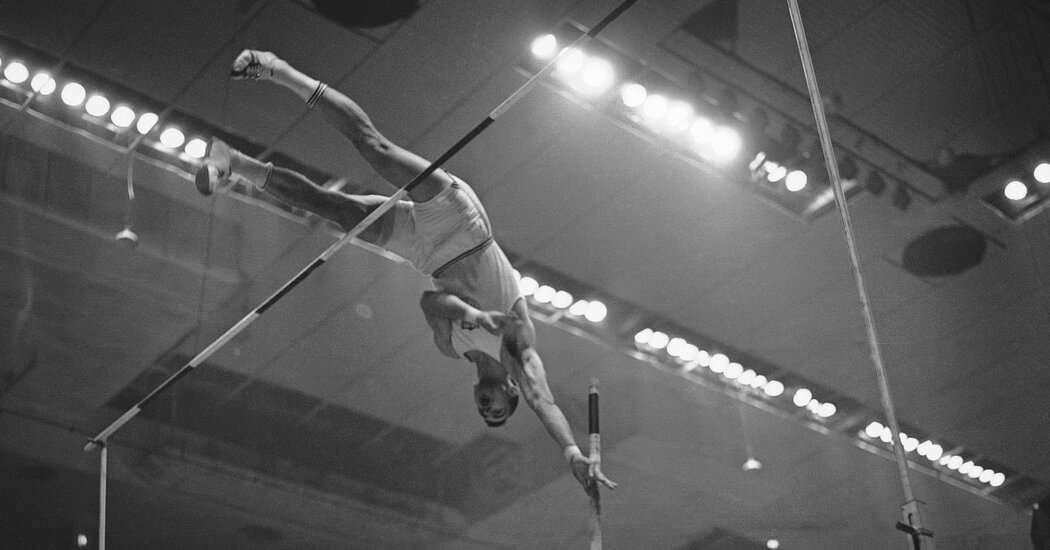

Uelses (pronounced YOOL-sis) landed in the national spotlight in February 1962, when, as a 24-year-old Marine corporal, he became the first pole-vaulter to clear 16 feet. The round number had a tidy appeal, and Uelses, though German-born, had the look of a clean-cut idol of postwar America.

He achieved that feat on Feb. 2, 1962, at Madison Square Garden in New York at the Millrose Games, one of the world’s most prestigious indoor track meets at the time. It was a winter night so cold that Uelses’ poles stiffened when he carried them to the Garden from his hotel a few blocks away on Manhattan’s West Side, when the Garden was on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets. He loosened them by putting them on a steam radiator in the Garden’s basement.

Uelses started the competition at 14 feet 6 inches and missed twice before clearing that mark. He then had the bar raised to 16 feet ¼ inch, and again missed twice. But on the third try (three attempts were allowed at each height), he made it, to screams from the capacity crowd. Moments after he landed in the hard sawdust pit, chaos erupted.

“The chief field judge ran to the pit to pull him out,” recalled Howard Schmertz, assistant to the meet director (his father, Fred), speaking to The San Diego Union-Tribune in 2012. “When he did that, all these photographers ran in after him. One of them hit the upright and knocked the bar off. The upright was bent, and the height wasn’t measured after the vault.”

As a result, his record was not technically legitimate, though no one doubted that he had established it, beating his own previously held record of 15 feet 10¼ inches. The next day, The New York Times proclaimed on its front page, “Marine Becomes First to Pole Vault 16 Feet.”

Uelses was unfazed by the technicalities in any case: He’d just vault higher the next night in Boston, he said. And he did, clearing 16 feet ¾ inches.

A Hearst “News of the Day” newsreel from that year captured his place in the public imagination. To the sound of horns and bursts of applause, an announcer proclaimed Uelses “the happy world-record breaker” and described his “personal quest of space” to an “unheard-of peak.”

Much was made of his military status. His commanding general in the Marines even took on the duty of sending out invitations to Uelses’s news conferences.

“When he turns out in uniform of the day for his regular chores,” Time magazine reported in 1962, Uelses “is a run-of-the-regiment Marine. When he strips to his skivvies and turns out for a track meet, the dark, handsome, Berlin-born pole-vaulter is the pride of the corps.”

Time added that he was receiving 300 letters of fan mail a week. He appeared on the cover of the Feb. 26, 1962, issue of Sports Illustrated.

The next month, Uelses became the first pole-vaulter to clear 16 feet outdoors, in Santa Barbara, Calif., reaching 16 feet ¾ inches again, his career personal best.

His triumphs were questioned by purists and some of his rivals, who objected to his use of a relatively new fiberglass pole. It was lighter and provided greater bend than the bamboo, steel or aluminum alternatives.

“Uelses isn’t a great vaulter,” the previous record-holder, Don Bragg, who used an aluminum pole, told Time. “All he did was perfect a gimmick.”

Uelses countered: “Let Bragg do the talking. I’ll do the vaulting.”

Hans Feigenbaum was born in Berlin on July 14, 1937. His father, a German soldier, was killed during World War II. When Hans was 11 or 12, his mother sent him to Miami to live with an aunt, who adopted him. He changed his first name to John and took the aunt’s married name, Uelses. Because he spoke no English, he started school in Miami in fourth grade. He later became a United States citizen.

He was introduced to the pole vault as a high school senior. The first day, he cleared 10 feet 6 inches. By season’s end, he reached 13 feet and won the Florida high school championship. Then came the Marines, and then one year at the University of Alabama. He said he left Alabama because he had received no coaching; “all they cared about was football,” he said.

After transferring to LaSalle University in Philadelphia, he became an N.C.A.A. champion. He graduated in 1965. During the Vietnam War, he was a Navy fighter pilot, and in later years coached high school vaulters.

The current world-record holder in pole-vaulting is Armand “Mondo” Duplantis, 23, of Sweden. His current best mark, set this year, is 20 feet 4 inches (listed as 6.22 meters). Like most pole-vaulters today, he uses a fiberglass pole.

In addition to his daughter, Ms. Robertson, Uelses is survived by his wife, Mickey Uelses: a brother, Fred; a son, Mark; two grandsons; and one great-granddaughter.

Weeks after Uelses’s moment of glory at Madison Square Garden, John Glenn orbited the Earth.

“He was the second Marine astronaut to go into space,” Uelses told The San Diego Union-Tribune. “I was the first.”

Frank Litsky, a longtime Times sportswriter, died in 2018.

Alex Traub works on the Obituaries desk and occasionally reports on New York City for other sections of the paper. More about Alex Traub

Source: Read Full Article