The hunt for Nazis in New Zealand started long before recent revelations about Willi Huber, the former Waffen-SS soldier who helped found the Mt Hutt skifield. By Anthony Hubbard.

A few years ago, Wayne Stringer stopped to help an old man who had collapsed outside the Oamaru post office. The man was a Lithuanian, “from Kaunas”. “Whereabouts in Kaunas?” said Stringer, a former policeman who had gone to Lithuania to gather evidence about suspected Nazis living in New Zealand. “From Užusaliai,” the man said.

“I know what happened in Užusaliai,” said Stringer. In September 1941, there was a massacre in the small town by a Nazi-led Lithuanian police battalion. Jonas Pukas, a member of the battalion who settled in Auckland after the war, almost certainly took part in that massacre and many others. Stringer and another cop had been to the forest where the shooting took place.

“How weird is that?” Stringer now asks, amazed by the coincidence of meeting someone from that obscure and bloody spot on the other side of the Earth. He didn’t tell the man why he had been there – he didn’t want to upset him.

But in any case the frail old man, “well into his eighties”, didn’t want to talk about the Jews. “That’s all in the past.” Stringer helped him into an ambulance and never saw him again. He wasn’t surprised about the attitude, though. Many Lithuanians don’t like to talk about that part of their history.

Stringer led New Zealand’s hunt for Nazi war criminals, and Jonas Pukas of Lithuania was his prime suspect. In 1990, the American Simon Wiesenthal Center gave to the Labour Government a list of eight Nazi killers it believed were living in New Zealand. The Listener broke the story a few days earlier and there was an immediate uproar.

The Center’s Nazi-hunter was Efraim Zuroff, a New York-born Orthodox Jew who doesn’t answer his phone on the Sabbath. Zuroff, you could say, is combative. He has infuriated governments all around the world for more than 40 years. Eventually, he sent dozens of names to Wellington, and he is scathing about New Zealand’s response.

“To simply walk away from the issue, as New Zealand did,” he told the Listener this month from his office in Jerusalem, “is an insult to the victims, their families and those who sacrificed their lives to defeat the Third Reich.”

But did New Zealand walk away?

"A horrible little man"

Stringer had two long interviews with Pukas at his home in Auckland’s Northcote in 1992. “He was a horrible little man,” says the retired policeman, one of two cops appointed to investigate Zuroff’s list. Pukas was a spry and wiry 78-year-old whose English was primitive even though he had lived in New Zealand for 40 years. His answers mixed flat-out denials of well-documented facts with weirdly specific details about mass murder.

The Jews of Minsk “screamed like geese” as they were being shot, Pukas told Stringer and a Scottish policeman investigating another battalion member in Britain. Pukas had not seen the Jews but he had heard them, he said, making the sound of the birds wailing or crying. They “fly in air”, he said, laughing. “Some of the Jews used to scream like that, like the geese,” says the official transcript of the interview.

Pukas admitted he was a member of the 2nd Lithuanian Police Battalion. He denied that the battalion had ever taken part in massacres. At first he denied being in Slutsk, site of a notorious massacre near Minsk; then he said he was. But he was only there because he had been teaching German officers in Minsk to ride horses and they had decided to ride to “the nice little town” of Slutsk for lunch.

All this, says Stringer, is “bullshit”.

The Slutsk massacre is one of the most infamous of the war and is massively documented. The killings offended even some of the Nazis. The local German area commissioner, Heinrich Carl, was so disgusted by the “indescribable brutality” of the killing that he wrote to his superiors: “I beg you to grant me one request: in future, keep this battalion away from me.”

There were “dreadful scenes”, says a summary of the facts by a German court after the 1961 trial of war criminal Franz Lechthaler, whose German troops led the Lithuanian battalion in the killing. Lithuanian soldiers herded the Jewish men, women and children into the marketplace.

“The Jews … tried to cling to fences, rafters, trees and the corners of houses, weeping and screaming and wailing all the while. Children, weeping and screaming, clung to their mothers. The Jews were torn free with brutal force by the Lithuanians and driven on with blows.”

They were taken to the place of execution and shot by a Lithuanian firing squad. “A thin layer of soil was then thrown over those who had been shot. When this was done, the next group of Jews was brought from the town to the place of execution.

“They, too, had to get down into the graves and lie face down on the bodies of those who had previously been shot and lightly covered with earth. Then they were shot with rifle fire by the Lithuanians. When one grave was full, the next was used.”

There is no doubt that Pukas’ battalion took part in the killing.

Particularly nasty duties

Pukas is listed in Lithuanian army documents as a machine-gunner in the first company of the 2nd Battalion, later renamed the 12th. And each company took part in the killing at Slutsk, as battalion member Juozas Aleksynas told Australian war crimes investigators in 1990. “All members of all three companies were involved. The members of the company would be rotated between shooting and guarding. When each member had a turn at shooting, they would start the process again until all the Jews had been executed.”

Pukas’ company was perhaps the worst. The Nazis used it more than the battalion’s other two companies for “particularly important duties” of extermination, historian Conrad Kwiet told a US court hearing into first company lance corporal Juozas Naujalis.

The battalion also took part in the murder of Jews in October 1941 in Minsk. Pukas told Stringer he had seen pits there with bodies in them. “One place they dug the holes very deep, as tall as the ceiling here. [The house is an old one with a high stud],” says the transcript. “They shot them in the daytime and then at night. Then they used to fill up the hole with bodies, shot bodies, and then they put lime on top.”

Asked if he saw this, Pukas said: “No, I didn’t, others told me.” At one point he talked about an “elite unit” shooting the Jews. “You’d see heaps of flesh and you would eat meat afterwards; we didn’t want to see it. There’s not much pleasure when you see those heaps of flesh flying; you wouldn’t go near them. Not interested to see heaps of bodies. And there were nice females. Nice girls and everything.”

Stringer asked: Were the nice girls alive or dead when he saw them? “No, they were alive. It wouldn’t be nice to …” The girls were Jewish girls he saw in Minsk wearing the yellow star, he said.

Stringer’s report noted that Pukas contradicted himself, was vague at crucial points and had “convenient” lapses of memory. “All in all, Pukas retains a lot of his native cunning,” Stringer wrote. “It was obvious from some of his comments that he was in very close proximity to Minsk and it is hard to believe he was not involved in some way.”

Told that other members of the battalion had said they took part in the shooting, Pukas “laughed loudly and said: ‘Maybe they were skiting that they were good soldiers.'”

The battalion was at the centre of a notorious and long-running case in Britain. Scottish Television screened a documentary about Antanas Gecas, a lieutenant in the battalion, showing he had taken part in many atrocities, including at Minsk and Slutsk. Gecas sued for libel but lost. The Scottish judge, Lord Milligan, found that Gecas had been guilty of war crimes.

Pukas knew Gecas and told Stringer that Gecas was “a good man, beautiful man”. Gecas was a “nice tall guy, lovely man, very friendly man, so I never can forget”, Pukas told me in an interview outside his house in 1992. He had spoken to Gecas “every day”.

Today, Stringer just says flatly that he thinks Pukas was guilty. The circumstantial evidence is too great and Pukas’ evasions too transparent.

Set up to murder Jews

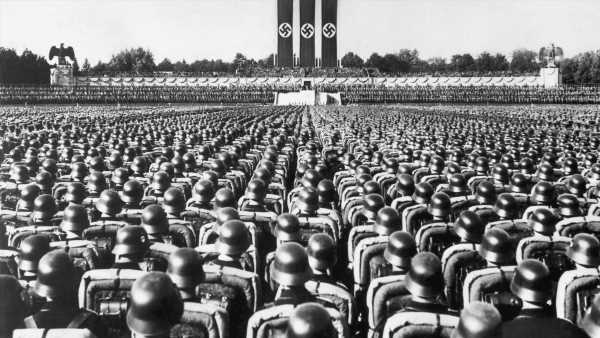

The battalion was one of many volunteer murder squads set up by the Nazis following the German invasion of Russia in June 1941. Led by the notorious Nazi Einsatzgruppen death squads, they murdered hundreds of thousands of Jews in the Baltic lands, Belorussia, Ukraine and other parts of the Soviet state.

Some of the fanatical nationalists who ended up in the police battalions had started killing Jews even before the German invaders arrived. The Nazis organised them into military units, as SS brigadier Franz Stahlecker said in a report to Berlin, for use in “the fight against vermin – that is, mainly the Jews and the communists”.

The Lithuanian Police Battalion, in other words, was not just incidentally involved in murdering Jews. Murdering Jews was what it was set up to do.

The careful German commanders of the Einsatzgruppen wrote detailed reports about the massacres, listing the Jewish men, women and children they murdered at each place. In Užusaliai on September 11 and 12, 1941, for instance, SS colonel Karl Jaeger reported the killing of 43 people in a “punitive action against inhabitants who supplied Russian partisans and who in some cases were armed”.

This may suggest that the killing was part of a military campaign against military opponents. In fact, the vast bulk of the killing was execution of helpless villagers. Between June and December, Jaeger reported, the Germans and Lithuanians killed 133,146 people in Lithuania, most of them Jews. More than 29,000 were children.

US Holocaust scholar Raul Hilberg, an expert witness at the Gecas trial, told the Listener in 1992 that the work of the battalion “wasn’t much of a military campaign”. “Why were they reporting the killing of hundreds of people after some such expedition when they didn’t have a single casualty of their own?”

The evidence suggests that Pukas was in the village of Užusaliai on those two terrible days. He is listed in battalion documents as going “off rations” during that period. This was the phrase applied to soldiers going out of their base in Kaunas on an “action” (the Nazi euphemism for execution).

Pukas, confronted with these details, produced a blur. He couldn’t remember anything about Užusaliai or any other town. Other members of the battalion had told both Russian and American courts about the slaughter in the village.

In more than 30 years as a policeman, Stringer told me in 2006 in an interview, he had found “there is a seed of guilt, and with everyone who is guilty of something, funnily enough, they always want to admit it. There is this compulsion to admit it – but in admitting something, you always want to minimise your involvement.”

So Pukas talked about bodies and flesh and shooting and then denied he had seen anything.

Pukas believed that Jews betrayed Lithuania when the Soviet Union invaded the previously independent nation in 1940. As a result of this betrayal, thousands of Lithuanians were arrested and sent to Siberia. “Jews want to make Lithuania another Israel … Jews take this another people’s ground.”

The Jews had power under the Russians and could play all sorts of tricks. “You open mouth [about the Jews] you get shot … Jews’ money talk – no can hit Jew. Jews got good friends, police chiefs.”

The myth of the Red Jew is a standard anti-Semitic trope still common in Lithuania, which suffered half a century of brutal Soviet rule before gaining independence in 1991. Some Jews did in fact hold important positions in Stalin’s police state. But Stalin also murdered many Jews and sent many to Siberia.

There were no living witnesses to tell a court what Pukas did during the war. Stringer worked closely with many other Western Nazi-hunting police units; all had taken a close interest in the battalion. But nobody from the battalion could remember Pukas – or nobody said they could.

NZ "had other options"

So it was that New Zealand decided to end its hunt for the war criminals. The then Solicitor-General, John McGrath, QC, said in 1992 that there was “no realistic possibility of further evidence being obtained in the case”. He even claimed that none of the suspects investigated by the police were guilty even on a prima facie basis of committing war crimes. However, he did say one [unnamed] man was probably present when a war crime was committed and it was possible he was involved in this “culpable homicide”. He meant Pukas.

Attorney-General Paul East said the fact that Pukas had “co-operated fully” with the authorities “would tend to support the story … that he wasn’t involved in war crimes. It’s also fair to say that he was a private in this particular battalion.”

We have seen that Pukas’ “full cooperation” amounted to massive evasion and denial of hard facts. And his having been a private hardly helps. The privates did most of the shooting – they always do – and thousands died at their hands.

Did New Zealand “walk away” from the problem of Nazi war crimes?

Zuroff says New Zealand had other options even if it could not prosecute. It could have deported or extradited Pukas on the grounds that he had lied to immigration officials when he entered New Zealand. “I can assure you,” Zuroff says acidly, “he didn’t write, ‘I was a member of a mass murder squad.'”

US policy is to strip the citizenship of Nazis who lied to US immigration officials about their past and then to deport them. Zuroff likens this approach to the prosecution of gangster Al Capone for tax evasion. “Americans made tremendous efforts to get Al Capone for murder, and they couldn’t do it. He was a murderer, but sometimes the law doesn’t allow the maximum punishment. There’s other ways to do it.”

The US deported half a dozen members of Pukas’ battalion to Lithuania in the 1990s and early 2000s. Two were found too ill to face trial. Court proceedings were begun against some, but death got them first. The critics said that Lithuania deliberately dragged the chain. Some other old Nazis deported to Lithuania lived there for years without ever getting a visit from the police.

American resident Juozas Naujalis, who was in the same company as Pukas, also claimed he wasn’t present at the Minsk massacres. Instead, he told a US court in 2001, he was guarding a railway station in Minsk against possible Soviet attack. The court found this claim “implausible” and “inherently improbable”, and he was deported to Lithuania that year.

Stringer says he never heard any discussion about deportation or extradition when he reported his findings to the Government. In any case, he says, “I don’t think New Zealand has got the balls to do that.

“I feel very let down by our Government. It was a good investigation, but they could have done something more,” he says. He didn’t say anything at the time. He was a policeman and the Government was his employer. But “the Government just wasn’t really interested”.

Pukas died in a rest home in Glenfield, Auckland, in 1994, a little over two years after the police interviewed him. His admired superior, lieutenant Antanas Gecas, died in Scotland in 2001, nearly a decade after a Scottish judge had branded him a war criminal. The critics said Britain was also a reluctant Nazi hunter.

Stringer is left with the haunting memory of the “screaming geese” of Minsk and the strange quiet in a grove of trees at Užusaliai.

“In this forest where it happened,” he recalls, “there was no birdsong, there was nothing. It was just silence.”

Source: Read Full Article

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/5J2SDA6X34W3XO7HNNMJJFLMOY.jpg)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/4BGMPVGXXE5Q6X3XQBJ6I56LMA.jpg)