Coal company Glencore has dismissed concerns of the state’s top heritage experts and intends to forge ahead with a plan to “relocate” a historic homestead and Indigenous site, associated with a frontier wars massacre in the Hunter Valley, to extend a coal mine.

In a move set to reignite debate about the social licence of mining companies to operate in heritage areas, the company intends to remove the Ravensworth homestead north of Singleton stone by stone and reassemble it in a nearby town.

The Ravensworth homestead in the Hunter Valley.Credit:Janie Barrett

The state’s Independent Planning Commission refused to approve the project last year, saying it would have “significant, irreversible and unjustified” impacts on the site’s heritage value.

But Glencore intends to fight a proposed heritage listing, and pursue new plans to extend its Glendell open-cut mine to access the 135 million tonnes of coal estimated to lie beneath the property.

The mining company’s case hinges on uncertainty around the location of a massacre that took place in 1826, when a posse of mounted police and settlers killed up to 18 Indigenous people.

The precise location of the massacre is unknown. The uncertainty has divided anthropologists and spawned a dispute between Glencore and the NSW Heritage Council over how to assess the site’s heritage value.

Glencore has won the support of Singleton Council – which voted to oppose a heritage listing for the homestead after receiving a briefing from the company at a meeting last month – and the company provided financial support to a community group that is lobbying to move the Ravensworth buildings to the town of Broke as a tourist drawcard.

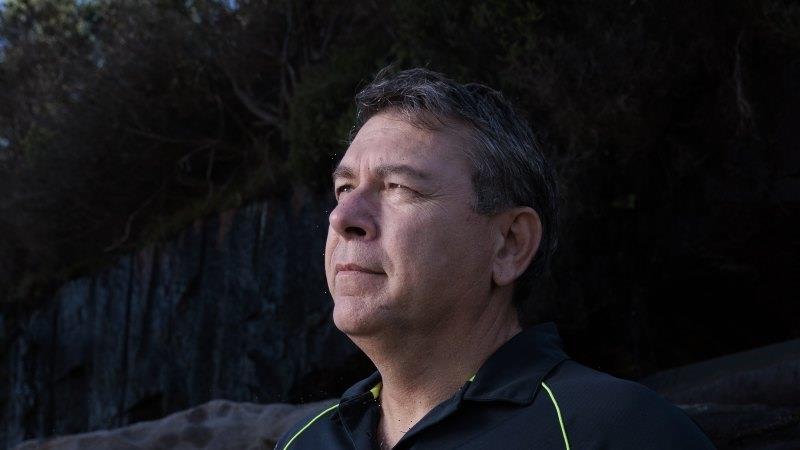

Scott Franks is fighting a plan to turn Ravensworth homestead into an open-cut coal mine.Credit:Brook Mitchell

Some Indigenous people who thought the site would be preserved after the planning commission ruling last October said turning it into a coal mine would desecrate a culturally significant landscape.

“This place is hallowed ground for us,” said archaeologist Scott Franks, an Indigenous man of the Plains Clan of the Wonnarua People. “Some of our people died here – they were disembowelled. There was fighting at a lot of points across the whole area.”

Some oral Indigenous traditions place the massacre at Ravensworth on the property owned by Glencore and which it intends to mine, while others place it further north or do not recall the massacre at all. Colonial records and contemporary newspaper reports contain some details about the 1826 killings, but are vague about the location.

“It is a central place in the colonial invasion and associated conflict and violence that resulted from the establishment of this and other estates in the 1820s, that led to the deaths of many Wonnarua people, as well as some colonists,” a heritage report prepared for the NSW Environmental Defenders Office by Flinders University Associate Professor Neale Draper found.

“Numerous conflict raids and reprisals, with accompanying fatalities in most cases, took place on the Ravensworth estate.”

The NSW Heritage Council, an independent statutory body, found that the evidence of a massacre on the site was inconclusive, but has proposed a heritage listing based on its importance in both Indigenous and colonial history.

Glencore told the Herald it will fight the proposed listing, saying the heritage council “does not present a balanced or factual assessment of the significance of the homestead and its surrounding landscape.”

The chair of the heritage council, Frank Howarth, said there were avenues the company could pursue within the heritage listing process to contest the heritage council’s assessment. If the heritage listing proposal was upheld, it would then have to be approved by the environment minister.

“The heritage council’s view was that the location of that specific massacre was uncertain,” Howarth said. “However, we were satisfied that there were undoubtedly frontier conflicts and incidents on the Ravensworth estate.

“It’s important to note that uncertainty about the specific location does not mean you can act in a detrimental way to the site.”

Glencore said it was assessing its options, which may include resubmitting modified plans for extending the Glendell mine.

The company is also under some pressure from institutional shareholders over the climate change impacts of the mine.

A group of large international shareholders, along with Australian shareholder Vision Super, has filed a shareholder resolution ahead of the Glencore annual general meeting in May. It queries the company’s efforts to curb its coal emissions and cites the proposed expansion of Glendell.

Glencore said it remained committed to the mine expansion, and said there was no way it could do this without shifting the homestead and its outbuildings, which date from 1832.

“Glencore believes that the best way to preserve the homestead is to relocate and renovate it, which would maintain part of its character and heritage value but give it a new lease of life as a repurposed venue,” a spokesperson for the Swiss mining giant said.

Singleton councillor Tony McNamara, who moved the motion to reject a heritage listing, would not comment in detail about the situation but said he saw it as the only way to preserve the Ravensworth buildings, which were falling into disrepair.

“What I can say is that these are beautiful old buildings and if they are left on site and if mining continues they will be destroyed,” McNamara said.

Singleton mayor Sue Moore said: “We’re of the understanding that the massacre wasn’t on the Ravensworth site but was quite a way off … We’re always open to new evidence should something arise, but that’s the council’s view. The best thing is for the homestead is that it be moved.”

A group of business people and local residents in Broke, south of Ravensworth, have been putting forward the town as a suitable site for the relocated homestead for several years.

An entity called the Broke Village Square Trust has been formed, plans drawn up and a petition circulated to gather support. The group was formed independently of Glencore but has received payments from the company for some planning work and says a grant from the company would support the operation of the Broke project.

Glencore said it had made “limited financial support” to the community group but rejected the assertion that it had been trying to create artificial grassroots support for moving the homestead.

However, it would cover the expected $25 million cost of the move, it said.

The uncertainty around the site has left Indigenous activists such as Franks in limbo.

“How can we have reconciliation when a foreign entity mining company has no time to consider the mental health impacts on First Nations people?” Franks said. “It’s abhorrent.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article