In its marketing material for a March sale of Native American art, Bonhams auction house offers prospective buyers a chance to take a “trip around the globe.”

The 10-day virtual auction, which begins Monday, features a wide range of North American artifacts: horn spoons and totems from the Northwest coast, baskets from California and pottery from across the Southwest.

Many of the objects — which run hundreds of dollars apiece — come from a late Denver collector and former University of Colorado professor who amassed a significant collection of Native American works from tribes across the American plains.

But a national Native American advocacy organization says dozens of these pieces represent tribes’ cultural heritage and it has called for Bonhams to remove them from the block. The auction house, though, has refused to engage, the organization said — part of a longstanding battle between tribes and those trying to cash in on their cultural works.

“They’re one of a few… auctions that refuse to work in productive ways with Native nations about the items they have for sale,” said Shannon O’Loughlin, a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and CEO of the Association on American Indian Affairs.

Bonhams did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Denver Post.

The association’s request comes as institutions across the country have faced mounting pressure to repatriate cultural items forcibly removed from Native lands — leading museums, universities and auction houses alike to rethink practices long considered the norm.

“A long, sordid history”

The Association on American Indian Affairs tracks auctions as part of its mission to protect the sovereignty and preserve the culture of hundreds of indigenous tribes across the country.

This work stems from what the organization calls a “long, sordid history of theft and looting of Native bodies and their burial objects from graves and other sensitive, sacred and cultural patrimony.”

Professors spent decades using Native American human remains as research materials for students. Funerary objects sat in museum galleries. Meanwhile, there were often few consequences for amateur archaeologists or looters digging up indigenous objects to sell or study.

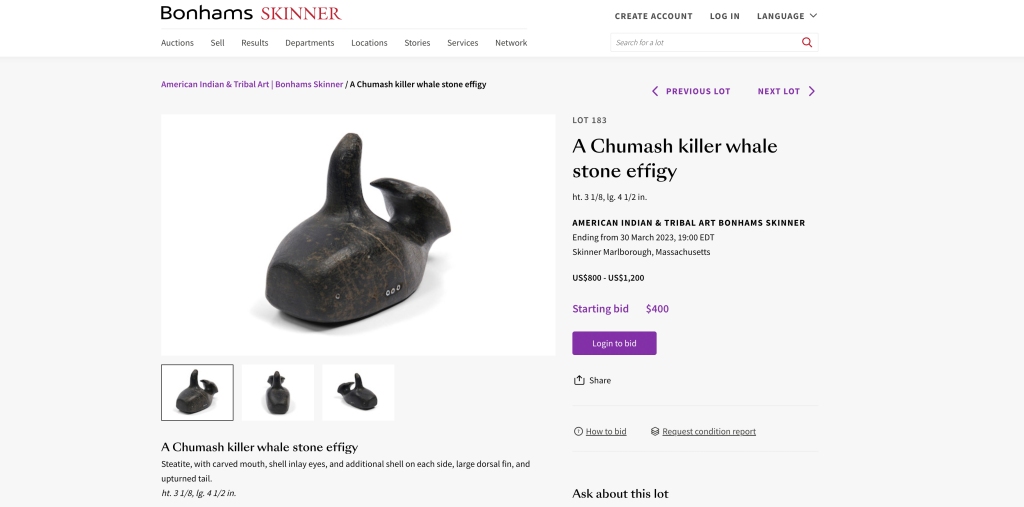

The Association on American Indian Affairs flagged 40 items in the Bonhams auction as potentially sensitive. These works include stone effigies, hide drums, pipe bowls and a host of other cultural objects.

“The trade in Native human remains, burial items and sacred and cultural patrimony is no longer a legitimate or worthwhile commercial enterprise,” the association said in a news release this week. “Moreover, businesses that continue to trade in sensitive Native cultural heritage perpetuate ignorance and racism and are active perpetrators that harm cultural and religious practices of Native peoples.”

O’Loughlin said the auction house did not respond to the association’s request to remove the items and will not work with tribes. Bonhams, she said, “purposely leaves out important information so that we can’t track or make reasonable claims to our items.”

Many of the objects on the association’s list come from the “Dean Taylor Collection.”

Taylor was a former University of Colorado Denver economics professor and avid collector of Native American art, particularly from the American plains. His pieces in the upcoming auction include 19th-century Lakota pipe bags, beaded Arapaho hide pouches and 20th-century girl’s dresses.

Other details about Taylor’s life and death were not immediately clear. The Post could not find information about his estate.

“He had a fabulous collection,” said Jack Lima, owner of the Native American Trading Company, a gallery in downtown Denver. Lima, who met Taylor in the early 1980s, said the professor inherited some of the collection but played by the rules as he acquired more items throughout his life.

“It’s addictive,” Lima said. “The art of indigenous cultures all over the world — people are fascinated by it. People become consumed by it.”

Taylor loved the material and history of these objects, said Linda Cook, owner of the David Cook Galleries in Denver, who sold Taylor items over the years.

Lima said he was skeptical of potential tribal claims over some of the items listed in the Bonhams auction.

“That’s not a sacred object — it’s a girl’s dress,” he said. “That’s questionable to me. Why should it go back to the tribe?”

“There’s not a lot of recourse”

Both states and the U.S. Congress have passed laws over the past several decades designed to crack down on the plundering of Native American cultural and sacred sites.

The Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, enacted in 1990, has given tribes an avenue to reclaim the remains of their ancestors and burial objects that have long filled galleries at America’s top universities and museums — though those repatriations have been far slower than expected.

But auctions operate in a murkier space, experts say. NAGPRA, as the 1990 law is called, only pertains to institutions that take federal funding and have legal control of the objects. Auction houses normally check neither of these boxes.

The FBI, under its Art Crime Team, can, and has, intervened to stop black-market sales of indigenous cultural pieces. These cases, however, are difficult to prove.

“There’s not a lot of recourse,” said Jan Bernstein, a NAGPRA consultant based in Denver.

The Bonhams fight is part of a long-running effort by tribes seeking to block sales of cultural heritage.

The Hopi Indians of Arizona, in a well-publicized battle 10 years ago, asked federal officials to halt a high-price auction of 70 sacred masks in Paris. The U.S. government, though, had little ability to intervene. Ultimately, a private foundation stepped in and purchased two dozen of them to return to the tribe.

“Sacred items like this should not have a commercial value,” Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, said at the time.

In 2014, an auction house in Canada removed a child’s blood-stained tunic from auction after blowback concerning the remnants of violence against First Nations being hawked as decorative art.

This year, the Association on American Indian Affairs has investigated 43 domestic and foreign auctions regarding more than 1,600 objects that were likely stolen burial objects or are cultural and sacred patrimony.

Raising alarms over these sales, O’Laughlin said, is about a “bigger movement to shift out of the accepted idea that it’s OK to sell” important indigenous items.

“What we’re trying to do is alert buyers about purchasing cultural heritage — that it’s not a good investment,” she said. “It’s not a good place to put your money.”

Get more Colorado news by signing up for our daily Your Morning Dozen email newsletter.

Source: Read Full Article