By Jordan Baker

Myall Creek Memorial.Credit: Rhett Wyman

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

When they first came together to mourn the dead of Myall Creek, it rained. “My husband said, ‘it’s tears of joy because they’re free’,” says Kamilaroi elder Sue Blacklock, a descendant of one of the two boys who escaped the 1838 massacre of 28 women, children and elderly men. “Their souls were free. They knew we were there, and they were not forgotten.”

Beulah Adams – whose distant uncle Edward Foley was hanged for his role in the killings – and her husband Ian shared that sense of unburdening when they stood with Blacklock in the rain, even as they grappled with Adams’ link to the murderous Foley. “New England is a very conservative place,” says Ian, who is in his 80s. “There’s still a denial about [what happened in the past], and there is still prejudice.”

The coming together of black and white to acknowledge the massacre at Myall Creek has been hailed as a triumph of reconciliation. Since Blacklock drove the establishment of a memorial at the site more than 20 years ago, their united voices have healed historical divisions. Now, people from all over Australia visit the memorial, where a gravel path winds through the sparse, beautiful landscape like a rainbow serpent to a massive rock overlooking the massacre site.

“The driving force is truth-telling,” says Ivan Roberts, a member of the half-Indigenous, and half-non-Indigenous memorial committee. “The road to the future travels through the past.”

However, the past can be a tricky place. Knowing what happened is one thing; accepting it is another. That tension plays out in the decades-long, bitter history wars over how to tell Australia’s story in school curricula, in the debate over the extent of the brutality on the country’s early frontier, and even among those living near Myall Creek. Recently, the memorial was vandalised. “[The vandals] didn’t like the word massacre, they don’t like the word murderers,” says Waabii Adele Chapman-Burgess, a Ngarrabul woman and member of the memorial committee. “A lot of those were scratched out.”

Australia is not the only country struggling with the darkness of its past. Japan, for example, is debating how to tell the story of World War II in its history books, worried that children will feel ashamed of their country. “These are terrible and painful truths,” says historian Anna Clark. “Coming to terms with them affects our sense of ourselves in the present. It’s not about what happened; it’s about who we are. Every generation has to work out what about its history needs to be passed on.”

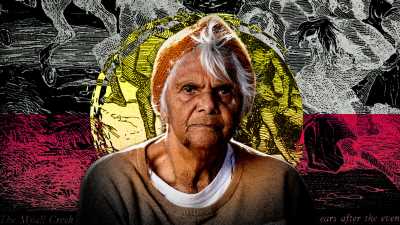

Ngarrabul/Gomeroi//Kooma woman Waabii Adele Chapman-Burgess.Credit: Rhett Wyman

Myall Creek is the most infamous Australian massacre of Indigenous Australians, partly because the rare trial and hanging of its perpetrators left comprehensive records. But it’s far from the only one. Over the past 10 years, as generational shame slowly fades and descendants come forward with details of crimes committed on their land, historians have confirmed almost 100 mass killings in NSW alone. At least 1500 people died, but it was “probably closer to double that”, says Professor Lyndall Ryan, whose painstaking verification and mapping of atrocities has transformed Australia’s knowledge of the frontier wars and cemented their place in the state’s history curriculum.

Ryan says the first massacre was in the 1790s and the latest in 1906, when at least six people – the threshold for a massacre – were given alcohol laced with poison.“The more you look,” says Ryan, “the more gruesome it gets.”

The study of massacres is a relatively new historical discipline. It grew after the 1995 mass executions in Srebrenica during the Balkan War when more than 8000 Bosnian men and boys were killed but no one knew for weeks. “There was a code of silence; the perpetrators shut down the whole village,” says Ryan. “The Europeans thought, ‘we can’t have a massacre after WWII, they’re only for uncivilised people’. Scholars began to think about [massacres] in a new way, that they’re carried out in secret.”

That code of silence also applied to Australia’s frontier wars, when premeditated, secretive killings became common as expanding stations encroached on traditional hunting grounds. “Breaking the code has been part of my job,” says Ryan. “Breaking the code is difficult.” She uses press clippings, journals from the European adventurers attracted to the exotic Australian bush, and, increasingly, long-hidden letters from conscience-stricken landowners, which are now being handed over by a generation that no longer fears exposure or shame.

Most massacres involved planned attacks on Aboriginal camps at dusk or dawn, and the burning of bodies to hide the evidence. As the years passed, and as weapons and tactics became more sophisticated, the number of victims swelled. Conflict over food and land were not the only triggers. “[They were] taking Aboriginal women for sex,” says Ryan. “That never changes over the whole period of the massacres. Some of the women get killed, of course, and others produce children, and many of those ended up in the stolen generation.”

While the atrocities at Myall Creek were well-documented as perpetrators were tried and hung, it was still forgotten for more than a century by everyone but the local Indigenous people themselves.

Blacklock was raised with the story, although she remembers children being told never to speak of it to outsiders. “I remember a really old man, I think it was my great-great-grandfather, sitting around talking [about it],” she says. It had cut a deep wound; the grief, the shame over accusations of stealing, the refusal of many in the wider community to believe it. Even now, Blacklock abides by her elders’ rule that she stay away from the massacre site from late afternoon because of the spirits. “A lot of sadness,” she says, “a lot of fear. Is it safe for us to be out in the bush? Or will policemen on horses come and shoot us? The fear of the white man coming.”

Beulah Adams – whose distant uncle Edward Foley was hanged for his role in the killings – and her husband Ian.Credit: Rhett Wyman

It wasn’t until the 1960s that the records about Myall Creek were “discovered” by historians. The story took a further 20 years to seep into the wider consciousness. Even then, there was resistance.

“I think that people of my generation were in a bit of a state of shock,” says Ryan, who is in her 80s. “I could not believe something like this could happen in Australia.”

These days, students learn about conflict during settlement in year 8 history. Myall Creek is a fixture in textbooks. A new curriculum being developed by the NSW Education Standards Authority will intensify a focus on Aboriginal perspectives. The frontier wars are expected to be given greater emphasis. “Draft syllabuses for history, due to be released in term 3, have been developed with Aboriginal teachers,” a NESA spokeswoman said.

Inverell High School Indigenous studies students (left to right) Braydon Bateman, Dequin Morgan, Gab Westgreen and Mathilda.Credit: Rhett Wyman

At Inverell High, all that is happening already. Aboriginal studies is a popular subject thanks to the enthusiasm of its teachers, Wiradjuri woman Cath Jeffery and her son, Jack. They take students to the massacre site, hear directly from descendants, and encourage students to share their own stories. There are as many non-Indigenous students as Indigenous ones in the class. “[We have] nieces and nephews and grandchildren talking about their personal experience,” says Jack. “It makes it easier to understand and grasp. Education is a very powerful tool.”

Inverell High School Indigenous studies teacher Jack Jeffery with his mother Cath Jeffery who is the former Indigenous studies teacher.Credit: Rhett Wyman

The non-Indigenous students bring those perspectives home and challenge the entrenched beliefs of their grandparents. “With the non-Aboriginal kids going into Aboriginal studies, it’s changed our town,” says Cath. “It’s brought our town closer together.”

The success of the memorial has prompted descendants of other massacres to seek a similar acknowledgement of their history. Just six months before Myall Creek, on January 26, 1838, some of the same stockmen are believed to have joined mounted police in the slaughter of up to 50 people at Waterloo Creek, near Moree.

Kamilaroi elder Polly Cutmore grew up hearing stories of women and children running for their lives, a story many local non-Indigenous people refused to believe. “We didn’t know a lot of details, there was a lot of history that was kept from us because of the secrecy we had to have to protect ourselves,” she says. Now, however, Cutmore is writing a book, which will be released later this year. “There’s a lot of truth-telling to come out, both black and white,” she says. “White families are still holding secrets here in Moree.”

Kamilaroi elder Polly Cutmore at what is believed to be the site of the Waterloo Creek massacre. Credit: Rhett Wyman

Saturday is the 185th anniversary of the Myall Creek massacre. Blacklock will attend; Beulah and Ian Adams hope to do so too, despite their declining health.

Blacklock feels a sense of peace when she’s at the memorial site. Forgiveness can be powerful. “When Beulah [first] came out … I said to her, ‘it wasn’t your fault’,” Blacklock recalls. “It was your ancestors, not you. You didn’t pull the trigger. You didn’t burn them’.” Her son Nathan, the former St George rugby league player, feels that peace, too. “There was never any anger,” he says. “None of that. It was more of a sorrow, more like you could feel the pain. “Now I go out there, it’s like something has lifted from the area. There’s a calmness that I can’t explain. It has a healing effect.”

The modern-day calmness of Myall Creek.Credit: Rhett Wyman

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article