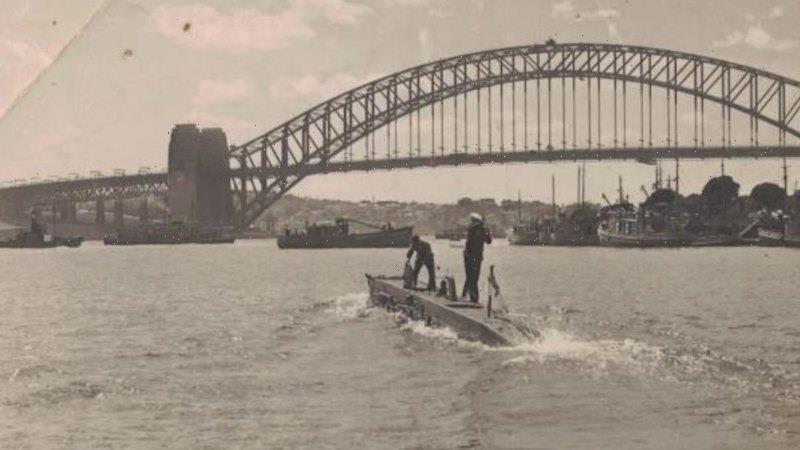

It is arguably one of the most intriguing wartime pictures to emerge in recent years. A midget submarine with two navy crew taking in the view of Sydney Harbour.

Allied midget XE3 submarine in Sydney Harbour, 1945.

This is three years after the Japanese midget submarines penetrated harbour defences in 1942 during World War II.

The image is of an Allied midget submarine X-craft used to cut underwater telephone cables used by the Japanese. The submarine was 16 metres long, had a displacement of 30 tons, a diesel engine and electric motor and was capable of 6.5 kts (12kmh) at surface. It had a crew of four which included a diver and carried two explosive charges which could be detonated remotely.

One navy source said: “The photo of an X-craft on the surface of Sydney Harbour with the bridge in view, given operational security surrounding X-craft, may be unique.”

The picture is part of a memoir that has emerged with the death on December 31 of submariner Sub Lieutenant John Beams, who operated with the flotilla of midget boats in the Pacific before they returned to Sydney after the Japanese surrender in September 1945.

From Worcestershire in the Midlands, he joined the Air Raid Precautions Civic Defence at the age of 13. He enlisted in the Royal Navy in 1943 aged 17. After initial training he transferred to the Isle of Bute in Scotland to train on X-craft (which were succeeded by the XE class), the idea being that they would be used to sink German warships.

Australian Lieutenant Henty Henty-Creer died commanding a similar midget submarine X5 after the attack on the German battleship Tirpitz in Altafjord, Norway, in 1943.

HMS Bonaventure (the depot or mother ship) and six XE-craft submarines sailed for Australia on 21 February 21 1945 via the Panama Canal. John Beams was 2nd Commanding Officer of XE-craft 3.

In his memoirs, Beams writes: “What took a little bit of getting used to was the security and secrecy that surrounded the whole training program.”

In Hervey Bay, off Bundaberg, divers experimented with cutting cables. “All in all, a very steep learning curve with little time,” he wrote. “Unfortunately in two days it cost two lives, Lieutenant David Carey and Lieutenant Bruce Enzer. They appeared to go berserk. It was put down to the fact that they were both extremely fit but overexerted themselves, and they were probably suffering lack of oxygen to the brain.”

Able Seaman Beams in 1943.

Dr Michael White, former Australian submariner and author of Australian Submarines: A History, was aware of the “remarkable” picture and said it represented people of enormous courage and ability.

He said the British submarine and the Bonaventure sailed up to Subic Bay in the Philippines. “One of the submarines with an Australian captain and diver then went on and cut the cable at great risk, off Vietnam. Another one later cut the cable at great risk at Hong Kong and that had a major impact on the war. The Allied midget submariners were the best of the best.”

Beams added: “With the return of the X-craft, operations were deemed to have been reasonably successful. We were all getting prepared for the next lot of operations. [On August 6] the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. On the evening of August 15 Bonaventure received the signal: “Cease hostilities against Japan.”

X-craft midget submarine operating at speed.

The Bonaventure was ordered to return to Australia. “We arrived in Sydney, anchored in the harbour. XE4 was put into the water with the end of the war, and they went to Sydney post-war. [We] as crew did some trial runs on the defence of Sydney Harbour at the heads. Then very hush-hush.

The orders were that the X-craft were to be taken off Bonaventure, some taken to Garden Island to be broken up. Rumour had it that four were broken up, one went on tour and one left on Sydney Harbour.”

John Beams wearing his service medals.

Mr Beam’s son, Dr Simon Beams said his father was demobbed to Britain after the war, but settled back in Australia in the 1950s with his wife Susan, a WREN whom he met training in Scotland. They also had two daughters, Jennifer and Diana. He worked in the rice and transport industries and later remarried and moved to the Gold Coast in his 70s.

Simon Beams said: “Undoubtedly there were other missions planned, the only thing that really stopped them was the atomic bomb. Their last days of the war were in Borneo. They were sitting there waiting for the invasion of Japan.

“If the bomb hadn’t dropped I am not sure whether our family would exist.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article