We like to talk about art as something we behold, but South African artist Zanele Muholi turns that concept fully around with the self-portraits currently on display at the Center for Visual Art: The photographs behold you.

Muholi does the staring, gazing directly at the camera lens and, by extension, the viewer. The whiteness of two eyeballs popping against dark skin, gleaming like the headlamps of a car coming toward you on a dark road is a contrast that the photographer enhances in the post-production part of the art-making process.

And while the eyes fix you, and invite you to consider the soul of the subject in the picture, it is the skin itself that drives the work. In these 80 photos, Muholi asks to be the Black everyman, or to de-gender that term, the Black everyperson, echoing, reflecting, considering what it means to be Black in the world, and within that female, African, lesbian.

If you go

Zanele Muholi, “Somnyama Ngonyama/Hail the Dark Lioness,” curated by Renée Mussai, continues through March 20 at the Center for Visual Art, 965 Santa Fe Drive. It’s free. Info at 303‐294‐5207 or msudenver.edu/cva.

The whole world, that is. These portraits were taken between 2012 and 2019 as Muholi traveled through cities across Europe, North America and in South Africa. The experience of being Black is different in these places, the photos suggest, but it is universally that of being distant, different, less than wholly human within the various white-supremacist cultures.

With the photos, Muholi is “reclaiming my Blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other,” as the artist says in one of the quotes displayed on the wall at CVA. “Just like our ancestors, we live as Black people 365 days a year, and we should speak without fear.”

To that end, Muholi (who identifies with they/them/their pronouns) indulges broadly in the language of portraiture as it has been employed over the centuries. There is the essence of Vermeer’s stirring intensity in the way they glance back over their shoulder in the photo titled “S’thombe, La Reunion, 2016.” There are reflections of the sort of reclining female nudes painted by Manet or Ingres in photos such as “Sindile, Room 206, Fjord Hotel, Berlin, 2017.”

There’s an aura of precious and pouty fashion photography in “Somnaya I, Paris, 2014,” which has Muholi bare-shouldered and donning a feathery headdress like a magazine model.

There are, in numerous photos, references to the tropes of ethnographic imagery that characterized published materials produced by Euro-centered anthropologists who ventured into Africa during in the late-19th and early-20th centuries — images that reduced indigenous Africans to easily-consumed, ethnic stereotypes.

It is these photos that stand out in this large and diverse body of work, and most pointedly show the artist’s skill at reclamation.

Muholi’s “Bester” series of photos, for example, shot in 2015, call to mind early illustrations meant to catalog hair types and facial features of Africans. The pictures mimic the submissive posturing expected of models as they were reduced — in the name of science, entertainment and journalism — from actual humans to exoticized illustrations of African culture.

But Muholi takes them back, and posits them in a more empowered 21st century. In “Bester V, Mayotte, 2015,” balls of steel wool used for scrubbing pots substitute for what might be the coils of braided African hair that captivated Western civilization. In “Bester I,” contemporary, wooden clothespins replace what could be a headdress and earrings.

And as usual, in Muholi’s photos, there is the stare that suggests: “I am watching you as you look at me.” The subjects get a say in this visual exchange. The exhibit’s title, “Somnyama Ngonyama,” translates from Zulu into English as “Hail the Dark Lioness” — and there is very much a sense of hunter being captured by game in this show.

The “Bester” series also has references to Muholi’s personal story, as do several of the photos that lean into family history. There’s the “MaID” series, which connects to the work of Muholi’s mother as a domestic, with the “ID” capitalized to show the images’ place in the artist’s self “identification.”

The personal, however, is only a part of the story. Muholi reaches widely with photos at or about historic events, ranging from racial injustices to segregated beauty pageants. One photo references the now-notorious death of African-American Sandra Bland, who was found hanged in a Texas jail in 2015. Another associates with the 2012 Marikana massacre, in which South African police killed 34 striking miners. The photo “Bayephi I, Constitution Hall, Johannesburg, 2017” positions Muholi behind bars at the prison where Nelson Mandela was twice jailed.

Muholi mixes political messages with environmental concerns and, in trademark style, connects current ideas to African traditions, making them timeless.

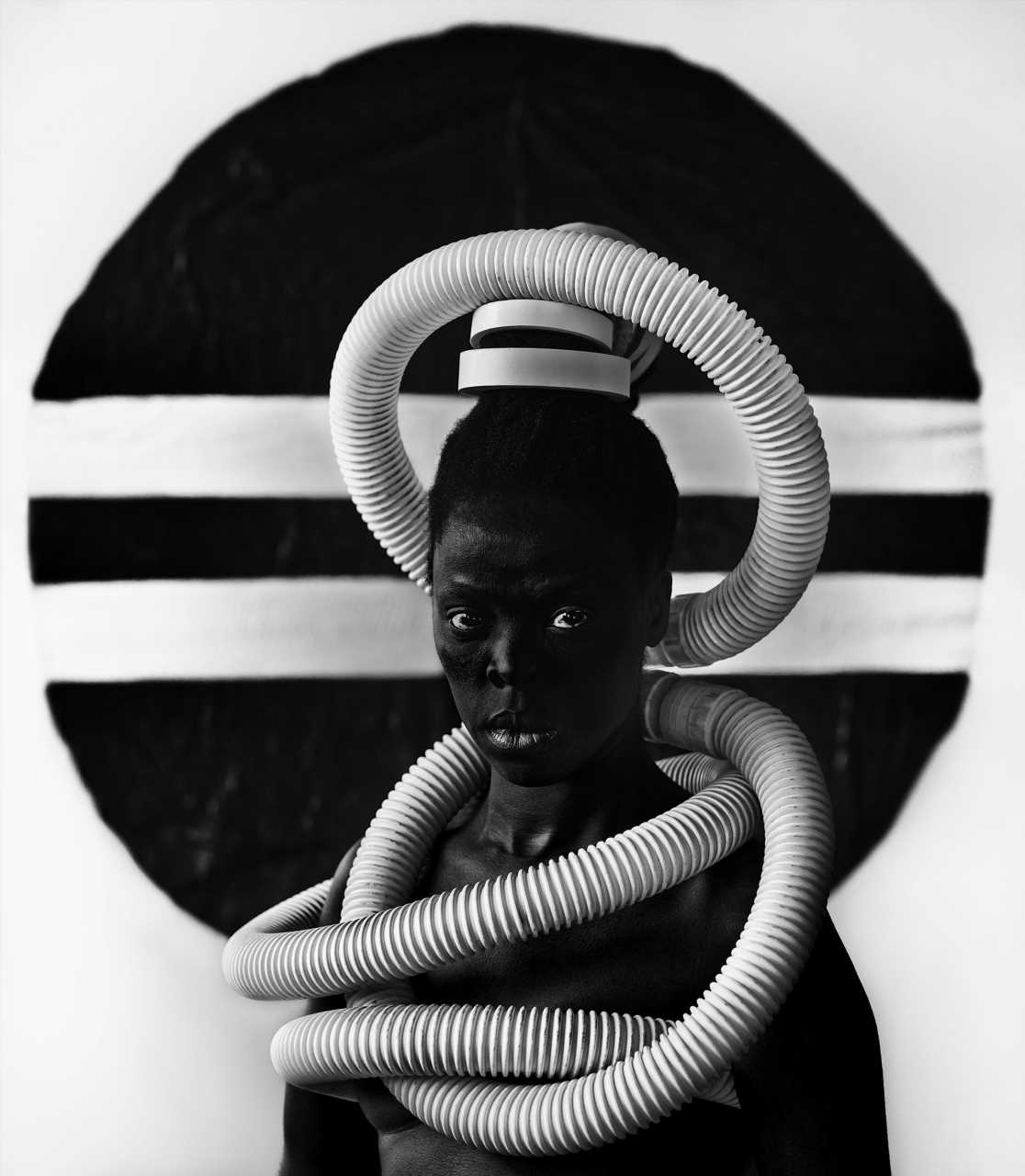

In “Sebenzile, Parktown, 2016,” Muholi wraps themself in a crown of what might be a vacuum cleaner or washing machine hose. In another, “Ziphelele, Parktown, 2016,” they ring their body with rubber tires. There are echoes of ceremonial apparel in both shots, though they also appear to raise questions about the health of a planet overloaded witih non-recyclables.

In that way, there’s a duality to all of the work. On one hand, it challenges viewers directly, eye-to-eye, but on the other it begs you to look and decipher symbols that give the photos added depth.

For example, “Bhekezakhe, Parktown, 2016,” has Muholi adorned in an elegant white necklace wrapped around their neck and bodice. Upon closer inspection, though, the jewelry is made from plastic cable ties, the kind that security forces now use to cuff prisoners.

It’s possible to find different meanings in these self-portraits and to apply them broadly, and this is where these images best resonate. The artist carries an unmistakable Africaness in this work, through both an emphasis on skin color and on attention to time-tested customs, real and imagined. But Muholi is a citizen of the world in these photos and forces us to recognize that, making the location of each shot — Oslo, Charlottesville, Sardinia, Philadelphia, Paris, Capetown — an official part of each photo’s title.

Muholi shows us that being Black is similar across the globe, and that its “otherness” crosses borders of place and time — as easily as the airplanes that carry artists to disparate destinations, and as seamlessly as one style of art or photography blends into the next.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, In The Know, to get entertainment news sent straight to your inbox.

Source: Read Full Article