Sheridan Smith’s shattering portrait of pain and rage: CHRISTOPHER STEVENS reviews Four Lives, the BBC drama that tells of families’ fight to catch serial killer Stephen Port

Four Lives

BBC 1, last night

Rating:

Stephen Merchant is wasted as a comic actor. But the beanpole sidekick to Ricky Gervais in shows such as Extras proves himself chillingly good in a true crime role.

His performance as serial killer Stephen Port in Four Lives (BBC1) has strong echoes of David Tennant’s superb portrayal two years ago of another monster who preyed on young gay men – Dennis Nilsen, in ITV’s Des.

It’s a far better drama than Merchant’s comic thriller The Outlaws, which he wrote and starred in last year.

In comedy he is limited, relying on gormless charm and a needy willingness to please. Whether on a chat show or a sitcom, it’s an irritating persona.

But as a loner whose social awkwardness masks his psychopathic urges, it’s creepily mesmeric.

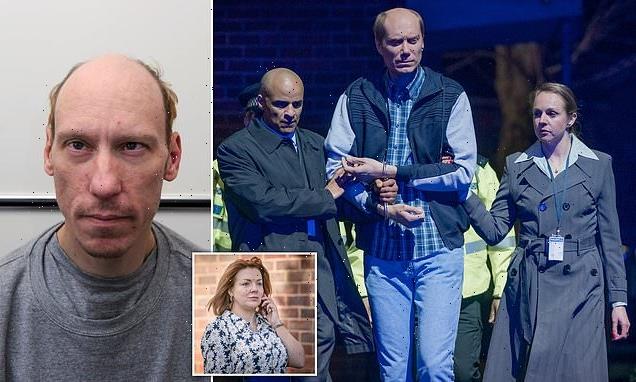

Stephen Merchant’s (pictured centre) performance as serial killer Stephen Port in Four Lives (BBC1) has strong echoes of David Tennant’s superb portrayal two years ago of another monster who preyed on young gay men – Dennis Nilsen, in ITV’s Des

With his small eyes lying heavily in their sockets like bruised grapes, and his sullen, hesitant speech, Merchant conveys a man whose words always lag several seconds behind his thoughts.

There is nothing flamboyant about the performance. Crucially, he doesn’t try for laughs, even when he’s indulging in his other obsession – buying children’s toys through eBay.

But he shows us the cunning that thrives in the killer’s slow mind, a cunning that the police completely failed to comprehend. Like his naive neighbour Ryan (Samuel Barnett), they see him as ‘a bit quirky but harmless enough’.

Port was a chef in his late thirties, who lured men to his flat in Barking through sex websites and dating apps. He drugged and raped his victims, before dumping their bodies.

Like Nilsen, he was as incompetent as he was callous. The body of his first victim, 23-year-old fashion student Anthony Walgate, was discovered in 2014 outside the front door of the flats where Port lived. The murderer reported it himself, in a 999 call. Yet the police seemed incapable of considering him as a suspect. In the first of three episodes this week, Four Lives makes it obvious that ingrained homophobia at the Met was largely to blame.

Once they realised that Walgate was a part-time sex worker, detectives treated his death as nothing more than a sordid misadventure.

Sheridan Smith (pictured) is Walgate’s heartbroken mum, Sarah Sak, certain from the start that her son’s death was not an accident

Like the Hillsborough drama Anne, running nightly on ITV, this story is seen chiefly through the eyes of a grieving, angry mother.

Sheridan Smith is Walgate’s heartbroken mum, Sarah Sak, certain from the start that her son’s death was not an accident.

It’s odd that these two dramas are airing at the same time, on opposite channels, because they mirror each other.

Both Sarah Sak and Anne Williams (played by Maxine Peake) are dismissed by authorities. It’s almost as if the motto of police forces from London to Liverpool is: ‘Just ignore her, she’s bound to be upset.’

Port (pictured) was a chef in his late thirties, who lured men to his flat in Barking through sex websites and dating apps. He drugged and raped his victims, before dumping their bodies

True crime drama treads a difficult line. It risks exploiting the victims and their families, glorifying the killer or lingering on the squalor of the deaths.

By concentrating on Sarah’s fight for justice, Four Lives avoids these pitfalls – though many viewers will find the implied emphasis on promiscuous sex difficult to watch.

A scene where Port and Ryan play with toy lorries as they discuss their fondness for ‘twinks’, or gay men who look like adolescents, is particularly unsettling.

Smith is in her element as the woman driven to find the truth, for fear that otherwise she will always blame herself for her son’s death.

She is keeping a lid on her hysterical grief but cannot stop it leaking out in her tears and her cracked voice.

When emotion that intense is channelled into a cause, a campaign, it becomes unstoppable. Watching Sarah Sak force the Met to care about her son will be an education.

Source: Read Full Article