Jonathan Larson died suddenly in January 1996, on the morning before his musical Rent played its first off-Broadway preview performance. A few months later, Rent would begin a 12-year run on Broadway and become one of the most successful musicals of all time. He never lived to witness its success, which makes it all the more remarkable that his project before Rent, tick, tick…BOOM!, is a story about the struggle between art and commerce. It comes to the screen courtesy of Lin-Manuel Miranda, who cast Andrew Garfield to play Larson. There was one tiny issue: Garfield had never before sung professionally.

DEADLINE: You had seen Hamilton. You had seen the level at which Lin-Manuel Miranda, Leslie Odom Jr., Renee Elise Goldsberry and the rest of the cast performed. And yet, when Lin asked you if you could sing, even though you had no professional experience whatsoever, you told him yes. What were you thinking?

Related Story

'Jockey's Clifton Collins Jr. On Doing His Own Stunts And Taking That "Leap Of Faith For Those Films That Matter"

ANDREW GARFIELD: I know [laughs]. Foolishness, pure foolishness. You’re right. You’re absolutely right. But I think it was the exact reason I had to say, “Sure, I can get there.” Because it was Lin, and because Hamilton was on repeat on my phone. There’s no way you can turn that down. It was in the peak of my obsession with Lin and all his brilliance, and I was just overwhelmed. I guess I knew somewhere deep down that I could get to a place where I could honor the thing. I knew I was a hard worker.

It wasn’t an immediate thing. Lin said, “Go and see Liz Kaplan,” who is the vocal consultant on the movie. “Go see Liz and see how it feels.” It was like an unofficial audition. And after the first session with Liz, she basically texted Lin and said, “I think he can get there given the amount of time we have.” That was it, really.

There’s also some kind of cliff-jumping, adrenaline junky thing about it for me. I love expanding. I love stretching. I love being scared. It’s not addiction, but it’s important for me. It’s life-affirming. And it’s a family trait; my brother’s the same and it’s how my dad is built. Try, fail, try again.

But can you imagine saying no to this? How devastating that would be down the line to see somebody else play this role? I rarely feel that with something, but this is one of the rare ones where, for whatever reason, I felt very compelled, and I think it helped that I felt such a personal identification and connection with the character of Jonathan Larson.

DEADLINE: What inspired that connection, do you think?

GARFIELD: So many things. The fact that I’m a creative person that has questioned, most days, whether I should be carrying on doing what I’m doing, or whether I have the chops, whether I’ll make it. How terrifying it still is to step onto stage or onto set, every time. Having to work through rejection and doubt. And then having that small voice inside, like Rilke talks about in Letters to a Young Poet, saying, “I must write, I must act, I must.” Whatever it is that we feel called to, that the world is testing us and really making sure we’re serious about that calling. It’s the artist’s initiatory journey. It’s like every single artist has to go through this over and over again.

It does feel archetypal in that way, and I think that explains why so many people feel a real kindship with Jon. I love that it’s a story about failure and rejection and carrying on. I find that so moving and beautiful.

DEADLINE: Jonathan Larson wrote tick, tick…BOOM! before he wrote Rent. And Rent has earned its spot in the pantheon of Broadway musicals, but the movie of his life might have been the story of the creation of Rent if he hadn’t written tick, tick…BOOM! and given us something that focused on his earlier failure. Of course, the irony of him writing this before Rent is that without that global success at the end of the road, he was delivering a deeply uncommercial musical about how hard it had been to write a musical that turned out to be deeply uncommercial.

GARFIELD: Exactly [laughs]. That’s how uncompromising Jon was, and probably why he was hard to be around at times, because that kind of clarity of vision and the transmission of egoless art is… well, it makes him very unique. He had to go through tick, tick…BOOM! and Superbia to get to Rent, and to get to the place where his heart can break open fully for his best friend, for a generation that had been lost to the AIDS crisis, to the abusive, inhumane [policies of the] Republican Reagan administration. He had the heartbreak necessary to write and create a truly great piece of art, but only by going towards it and falling into the thing he had been running from.

It’s that descent that is so interesting. We’re a culture obsessed with ascension, but descent is what we need. We’re a culture of Icaruses who are avoiding death and pain, and who have been sold this idea of the pursuit of happiness above all things. It’s a very shallow way to be. I’m not saying it should all be self-flagellation, but there’s a balance to be had to keep us truly earthbound.

DEADLINE: You played Prior Walter in a big revival of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. That play and Rent both came out of this horrific chapter in human history. It must take extraordinary courage to channel this kind of pain into art that resonates as much today as it did at the time.

GARFIELD: Yeah, channeling pain, if we meet it, moistens the soil. But only if we meet it, and that’s what happened with Jon, I think. It’s like he’s suddenly plunged into the depths of his own soil, and he has to wrestle with the humility of not being in control of things. But saying, “For whatever reason, I’ve got to fight for this thing. Got to wake up, got to write, got to sing, got to do it. Don’t know why, but I’ve got to do it.”

You may never experience the joy of it. You may not get the harvest. You may not get the flowers and the applause, but you don’t need it. All you need is to do what you do. And that’s governed by us.

It’s true what you say. After Superbia, tick, tick…BOOM! was an anti-commercial intention. It was like he had to reclaim and process. He says, “OK, I’m going to write something really fucking personal. I’m keeping all my own commercial needy demons at the door. They are not allowed.

This is a ritual for my family, my chosen family, my artistic family. This is for us. This is for my friend Michael, and everyone like him.”

I get chills, because that was how we approached and intended to create the movie. We had a week and a half at New York Theater Workshop, where Rent was about to premiere before Jon passed away. Where it got its first off-Broadway run. His spirit was still there, and we felt it. We said, “We’re going to try and meet this moment together.”

The struggle for Jon was that this show had to be pure. Commercial success or failure didn’t count because he was exorcizing what he needed to exorcize. It was vulnerable and it was exposed, and it was totally naked and without frills.

DEADLINE: This is Lin-Manuel Miranda’s feature directorial debut. Describe what the atmosphere on set was like.

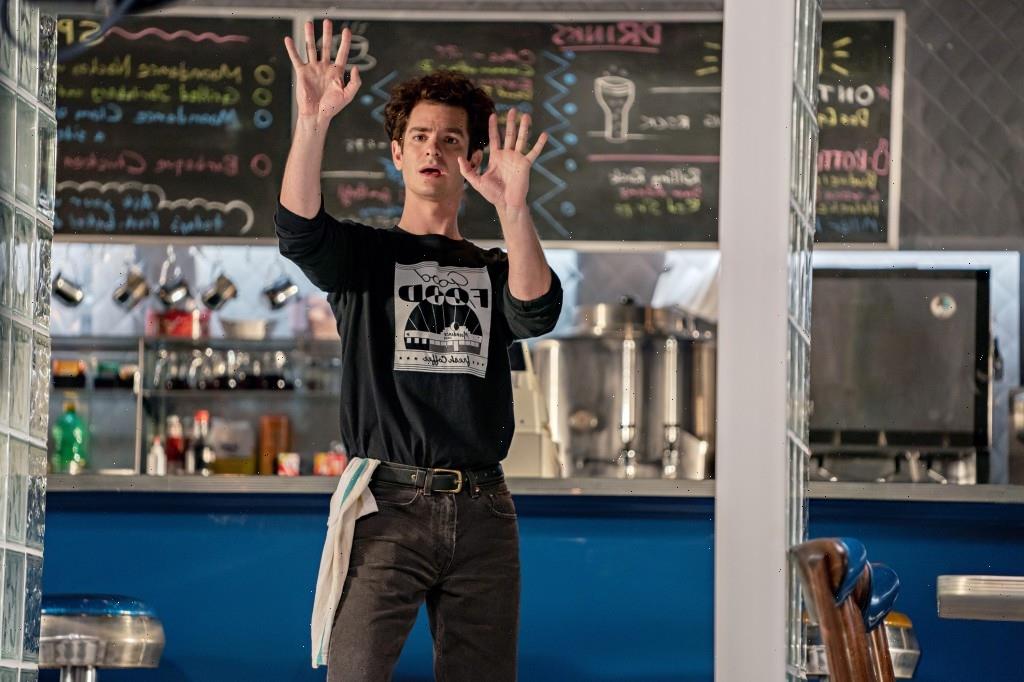

GARFIELD: It was everything you would imagine Lin to be and then some, like extra, extra, extra. I think about that glorious “Sunday” sequence at the Moondance Diner with a dozen or more cameos from Broadway greats. It was a deeply confusing thing for me as the actor in the middle of it. I kept on having to say cut, because there’s a lyric, “Sit the fools.” And I’m there looking at Joel Gray and the Schuyler sisters and Beth Malone. After 13 takes, where I would be in complete control of the diner, at that line my body would have an allergic reaction. I said, “Lin, I can’t do it. I can’t do this. You’ve fucked me up. This wasn’t written this way, to have all these legends present. It’s such a shit idea, and I can’t say it.”

He’s like, “OK, buddy, let’s go for a walk.” We went for the walk, and I said, “I can’t call them fools. You’ve given me a room full of geniuses and my body can’t do it. The song doesn’t make sense to me anymore.” He said, really simply, “No, no. You don’t know who they are.” I was like, “OK, let’s shoot.”

After that we did it in two takes and it was great. It’s one of the best sequences in the film, and it’s Lin’s. What I love about it is Jon wrote it to sing alone on a tiny little stage on a piano. So, in a way, that sequence was Lin’s gift to Jon at the edge of the cosmos. He wanted Jon to hear the song sung by this divine chorus of his heroes, harmonizing in the most beautiful way to reach the back row of the galaxy.

DEADLINE: You had the additional pressure of performing, for the first time professionally, in front of that chorus. How do you overcome the vulnerability of doing that?

GARFIELD: You just do it. But it’s the Jonathan Larson story, every single time. It is vulnerable. I remember being in rehearsals for Angels in America, and Tony Kushner came for the first run-through of the first act. After two weeks of rehearsal in a 12-week process. I’m in that very exploratory, open kind of place, and then suddenly Tony’s there.

We do the run, and he can’t make eye contact with me afterwards. I’m having a full meltdown. I’m interpreting it in all the worst ways anyone could ever imagine. I go for lunch, and I’m walking up and down the South Bank in London going, “How do I throw myself into the river and break my own leg without making it look like I did it on purpose? How do I never again set foot in that studio? How do I avoid this chasm that has just opened up before me?” And then I was like, “Oh, hi old friend. Here we go again.”

It has been like that every single time since I started. It goes back to Jon saying, “I’ve got to go back in. All I have to do is get back into the room.” I have no choice. I do, but I don’t.

And by the way, I think when you still step back into the room despite the gaping chasm that seems larger than ever, that’s a good indicator you’re close to something important. I think that’s what Jon was going through leading up to his workshop. He could feel something bubbling up.

Actually, there was a line that had to be cut from tick, tick…BOOM! after he died, which was, “Sometimes I feel like my heart is going to explode.” They cut it because his heart did explode. He was 35 years old. He knew. He was pressured and he knew. It’s those moments where, when we’re about to cross the threshold where we feel like we’re going to die if we go across that we know: we will die if we don’t.

Must Read Stories

Sandra Oh & Awkwafina Sister Comedy From Gloria Sanchez Lands At 20th Century

Netflix & Michael Starrbury Adapting Comic ‘The Hated’ For Potential Series

‘Cyrano’ L.A. Red Carpet Premiere & Upcoming Live Events Postponed Due To Covid

Daisy Ridley To Star & Produce Indie Drama ‘Sometimes I Think About Dying’

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article