The story goes that two feuding brothers owned a substantial lakefront property off the northeastern part of Indiana. One of them figured that the best way to get back at the other was to sell his portion of the land to Black people. No one has been able to verify if this legend is true, but regardless, that property, now known as Fox Lake, has been a historic African-American resort for close to a century. The official story is that Fox Lake, which is named after its original owner, Daniel Fox, was acquired by a group of white businessmen in 1924; established the Fox Lake Land Company; and promoted the area as a way to create a Black resort, the first of its kind in the state. In 1926, Black people started to buy lots of property and two years later, the first houses were built. The great-grandfather of Dr. Robin Newburn, founding member of the Fox Lake Historical Society, was one of those early pioneers in the area.

Newburn’s great-grandfather Ralph Jackson worked for a construction company and helped dig the hole for Fox Lake since the body of water itself was formed by glaciers. Her grandmother Martha Jackson was around 15 years old when the resort opened, and she married a Georgia migrant when an opportunity came up to establish their legacy. “They had rented from this one woman for many years. She got old and didn’t have any children, and her husband passed. She was ready to sell it, and she gave them a first crack at the purchase.” To this day, Newburn’s family has one of the oldest cottages on the lake. Furthermore, the majority of the landowners at Fox Lake are Black, with those individuals being second- and third-generation vacationers.

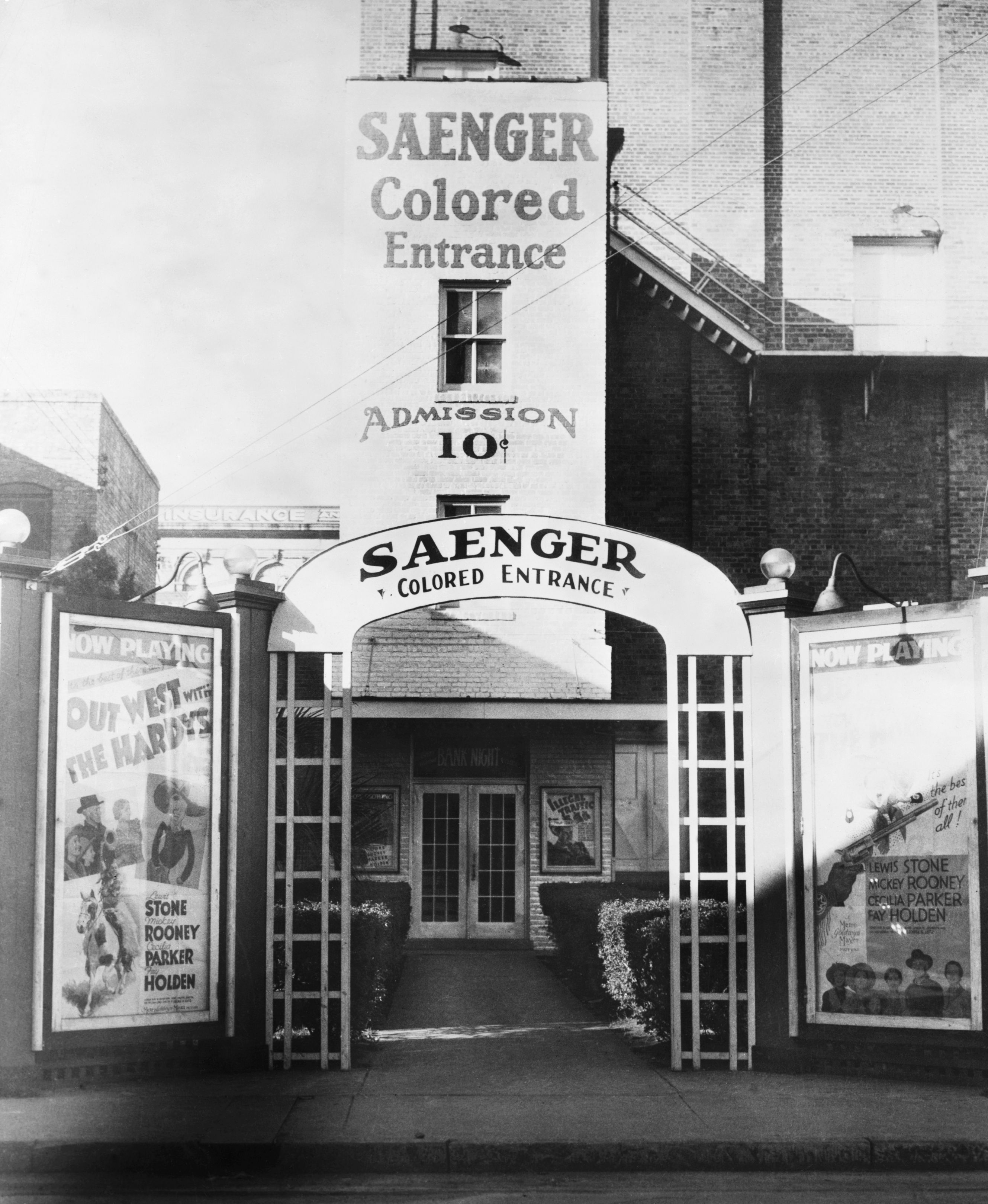

Under the tyranny of Jim Crow, there were restrictions throughout the country for Black people, especially when it came to entertainment. There are countless stories ranging from the likes of jazz icon Billie Holiday to actress Dorothy Dandridge having to take service elevators in hotels or being banned from certain restaurants and pools, because they were reserved for whites only. A Black journalist by the name of George S. Schuyler conducted an informal survey at the time of 105 “travel establishments” along the Northeast and found that not a single one among them would accommodate Black people. The prohibitive nature of public spaces—alongside the potential threat of white violence—is what led to The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for African Americans highlighting hotels, restaurants, and gas stations that were safe for them to stop at. But an aftereffect of this countrywide segregation was the birth of several African-American resorts that provided safe havens full of community and leisure.

According to The Guardian, traditionally, summers have been America’s most segregated season. Coastal cities such as, but not limited to, Norfolk, Charleston, and Miami, banned Black people from public beaches and neglected demands for Black people to have beaches of their own. If the town did respond, the pickings were disgraceful. For example, in Washington, D.C., Buzzard’s Point, a former dumping ground that was in proximity to a sewage plant, was the designated spot for the city’s Black locals. Also, the failure of the town to provide proper recreation for Black people often led to several drowning incidents where Black youths would go off wandering in unsupervised, dangerous areas. Further, the disparities could lead to rioting. In fact, the 1919 Chicago race riot began when white residents stoned a Black teenager named Eugene Williams for crossing into an area of water that was whites only. In 1968, Hartford, Connecticut-based Black people staged a series of protests as a response to multiple Black people drowning in an area of water near the housing projects where they resided.

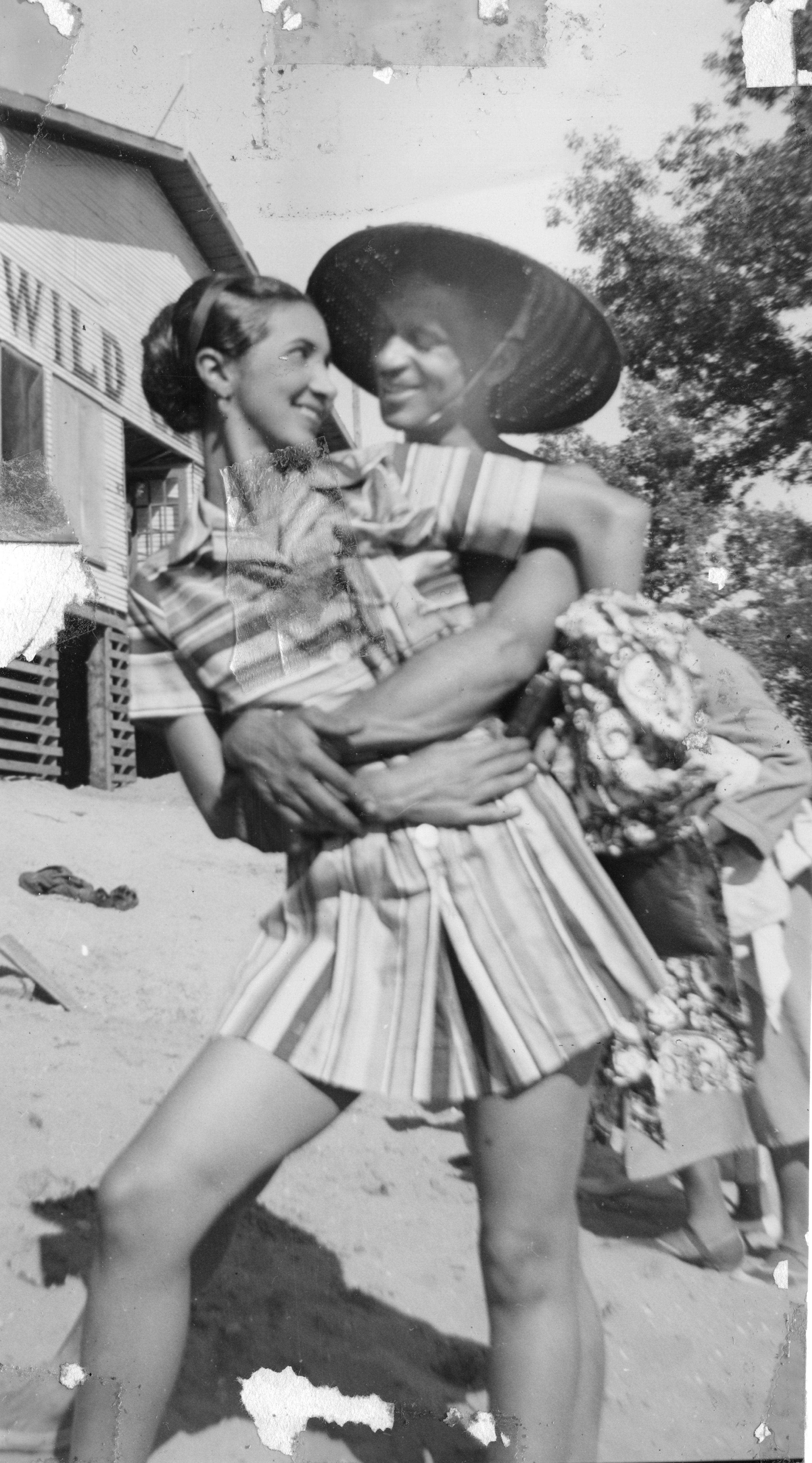

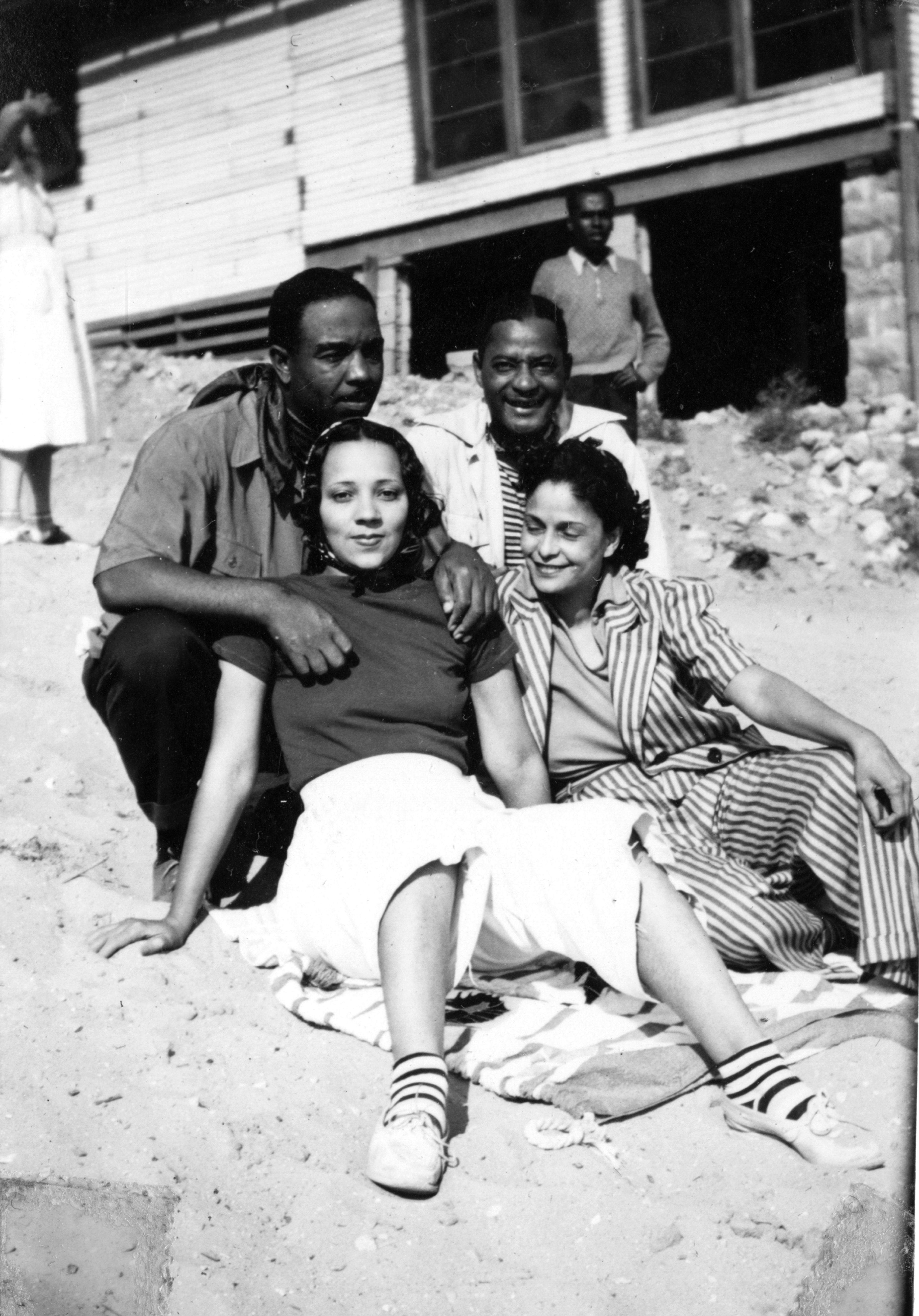

But for others who had the option of traveling to Black resorts, namely those who were formally trained and of middle or upper class, they flourished within the separation of races. The original visitors of the Fox Lake resort in Indiana were doctors, dentists, teachers, pastors, and attorneys, to name a few, and they came from not just the Hoosier state, but also Michigan, Ohio, and Illinois to have some fun. The original group of people at Fox Lake sought to market to African Americans who at least had graduated from high school, and many of them belonged to Greek organizations. Word of mouth along this echelon of society contributed to Fox Lake’s popularity, and those involved wanted to maintain that standard of professionalism and proprietorship for their descendants.

Fox Lake was included in The Negro Motorist Green Book, because the state of Indiana was a Ku Klux Klan stronghold. Jordan Fischer of WRTV, an Indianapolis news station, stated in 2017 that at the peak of Klan activity in the 1920s, 30 percent of “all native-born white men” were members. Even more recently, acclaimed actor Adam Driver said in a press tour for BlacKkKlansman that he saw Klan rallies while growing up in Mishawaka. In Angola, where Fox Lake is located, there was a lot of Klan activity. In Dr. Newburn’s words, “I have heard stories of Black folks being at Fox Lake and going into town and having some trouble. So it’s interesting to me that, you know, they [the Ku Klux Klan] wouldn’t come our way. They never came to the lake. … They never bothered anyone.” Its name became so prominent that those such as Duke Ellington and Joe Louis stayed at the resort, because they were denied access at neighboring facilities.

The same can be said of Atlantic Beach in South Carolina. Nicknamed the Black Pearl, the resort saw entertainers such as Ray Charles and James Brown, who would wine and dine with other vacationers hailing from the eastern part of the country. According to the Charleston City Paper, Gullah Geechee businessmen founded Atlantic Beach in response to what was denied to them by whites in the 1930s. Throughout the 1940s and ’50s during the summer weekends, Black folks would arrive by the truckloads. Vacationers could swim, ride the Ferris wheel or merry-go-round, and attend a cabaret or nightclub where, if they were lucky, they could hear Marvin Gaye within earshot.

John Skeeters, a historian of the area, remembers those good old days. His parents, who were originally from Wilmington, North Carolina, operated a restaurant and motel on Atlantic Beach. Born in 1935, Skeeters would observe his family feeding some of the aforementioned entertainers who performed at Myrtle Beach hotels, such as Ocean Forest, but could not stay there. But its bustling days are long gone. As Skeeters puts it, “The younger people did not redo what the parents left for them to carry their businesses. [There was] too much attraction that surrounded us.” The majority of Black locals moved away, and Skeeters estimated that there may be around 10 of those original people who grew up on Atlantic Beach left.

We didn’t have the foresight to realize that we should’ve maintained what we had

So, what was the attraction that surrounded the younger people if all that they wanted could be found right at the Black Pearl? The answer: desegregation. When the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, the landscape of Black vacation resorts in America changed—or disappeared—forever. At that point, Black people could enter whatever hotel lobby or swim in whichever section of the beach waters they pleased. As such, many Black-exclusive resorts began to lose their clientele and revenue. Some of the casualties were Idlewild in Michigan, also known as Black Eden; Bruce’s Beach of Southern California; and American Beach in Florida.

An aftereffect of this countrywide segregation was the birth of several African-American resorts

“We should’ve never assimilated,” Henrietta Shelton says. Shelton is the founder of the Chicken Bone Beach Historical Foundation, which is named after the only section of the Atlantic City beach where Black folks were allowed. Like Atlantic Beach, Black vacationers went to Chicken Bone by the busloads—and what they brought with them gave the spot its name. “Fried chicken,” Shelton says, “can be kept out in the sunlight all day and not be spoiled.” Some say that because cleaners of that section of the beach found so many chicken bones in the sand that that’s how Chicken Bone got its name. In the early 20th century, Atlantic City’s population and cultural significance rivaled those of Harlem. The bars were open 24/7, and entertainment was available all season. When it came to Chicken Bone, Sammy Davis Jr. and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were just two of many Black public figures who vacationed there.

As a child, Shelton remembers how thousands from Atlantic City’s Missouri to Mississippi Avenue would be on their way to the beach. The Northside of the city was replete with Black entrepreneurs who covered the bases of restaurants, barbershops and salons, dentist offices, and credit unions. It was, in her words, “a city within a city” from the ’30s to the ’50s. “We didn’t have the foresight to realize that we should’ve maintained what we had, ’cause we could not compete on that level. We really should not have just walked away.”

Black leisure is a necessary topic that underscores the threat—and liberation—of mobility

But not all Black resorts suffered. Lincoln Hills of Colorado, the only resort geared toward African Americans west of the Mississippi River, thrived throughout Jim Crow, the Great Depression, and desegregation. Retired judge Gary Jackson has a long, illustrious stake in that land. His great-grandfather William Pitts built a cabin in Lincoln Hills in 1926. The son of a slave master and one of his enslaved women, Pitts went to Colorado to visit his son who was staying in a Veterans Affairs hospital due to a World War I injury. During Pitts’s time, more than 600 lots were sold to families. Pitt paid $120 for three lots, each costing $40.

As a teenager of the ’50s and ’60s, Jackson and his parents would go to Lincoln Hills every weekend with his BB gun to shoot chipmunks and squirrels, go hiking, fish in the creek, and swim in the ponds. Prior to Jackson’s time, there was Camp Nizhoni, where not only African-American but also Hispanic and Japanese girls took part in nature-based activities under this particular YWCA branch.

Vacationers could swim and attend a cabaret where, if they were lucky, they could hear Marvin Gaye

To this day, Lincoln Hills still maintains a sterling reputation. When Barack Obama was nominated for president back in 2008, according to Jackson, 50 delegates from around the country convened at the resort. “When I got my law degree (from the University of Colorado Law School), I was one of the founders of my Black Bar Association, and we would take the lawyers up to our cabin to have retreats,” Jackson says. Robert Smith, one of the richest Black people in America, is a cofounder of Lincoln Hills Cares, a foundation that shapes the next generation in outdoor education and recreation. And, according to Jackson, he owns 80 of the more than 100 acres that comprise Lincoln Hills. So to this day, Lincoln Hills is still majority Black owned, and Jackson himself talks to various news outlets about his family’s legacy at this location.

Black leisure is a necessary topic that underscores the threat—and liberation—of mobility in this country. Who gets to go where and who gets to do what they want at that particular place has never been equal across the board for people of different races. Even to this day, Black Americans still face discrimination for simply existing in spaces with white people. Nevertheless, the importance of good pastimes and pleasures in spite of the systemic oppression needs to be acknowledged. Because although we may have toiled and suffered under the weight of racism, we were never crushed due to our ingenuity. We, as Black Americans, had fun when we were pushed into the margins of obscurity. Whether it was our forefathers building cabins, digging holes, or opening a restaurant and motel, we developed refuges for each other, and it is our responsibility to remember that labor.

Source: Read Full Article