A very Brrritish lockdown

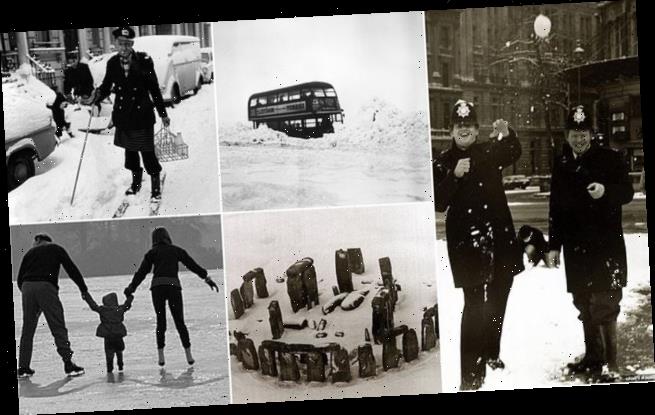

How to spoil the new year party: A stranded double-decker, Kent, 31 December 1962

The whole country was brought to a standstill for months at the end of 1962 – but for very different reasons to now. Author Juliet Nicolson recalls an extraordinary winter

It was Boxing Day 1962 when the snowflakes began to fall. It was our first Christmas at our home, Sissinghurst Castle in Kent. The house would later become famous for the garden my grandmother, the author Vita Sackville-West, created there, although at this time it was an extraordinary old wreck. I was eight years old and it was completely thrilling. Snow is always magical for children, not so much for grown-ups.

They were right to be wary. The snow fell for the next ten weeks, with blizzards, treacherous ice and temperatures plummeting to lower than minus 20C. There were moments when the entire country ground to a halt. Schools closed. People were separated from those they loved, or trapped inside with those they didn’t.

It was a very strange time. The world felt caught between the old and new. We had moved back to my grandmother’s way of life, which was essentially Edwardian: we ate meat pies (every supper was smothered in pastry) with steamed jam roly-poly pudding. My mother still kept her ration books and clothing coupons in her desk ‘just in case’ – as I imagine we will, in future years, have a drawer of face masks. Yet Elvis was shaking things up and Mary Quant was raising hemlines. There was a glimmer of a youthquake heading our way.

‘You’re under a vest’: Bobbies join a snowball fight, Trafalgar Square

We were happy but – like everyone else – lived with the constant fear of nuclear war. Many adults had lived through two world wars and felt another was on the horizon. New US president JFK had been warned that nuclear conflict with Russia would kill a third of humanity. In October 1962 he had negotiated with the Soviet Union to defuse the Cuban Missile Crisis – perhaps the closest the Cold War came to full-scale nuclear war – but the fragility of world peace felt very real and ever present. The adults tried not to speak of it in front of us, but we knew about the potatoes buried in the old air-raid shelter in the garden at Sissinghurst, and my six-year-old brother Adam and I had hidden some treasures there – my comb and his toy truck – just in case.

My grandmother had died in June, leaving Sissinghurst, complete with staff, to my father, Nigel. He had no money to pay them. He was a writer and had a wife – my mother Philippa – two children and another baby on the way. We lived in London, where we were at school, during the week, but felt that Sissinghurst was our true home. We lived in the grounds of the house in one cottage, with my grandfather Harold Nicolson (who we called Hadji, as my grandmother had) in the other.

Snowbound Stonehenge: ‘like sugar-covered biscuits’

Sissinghurst had fallen into neglect and it was freezing that winter: there was no heating besides real fires and electric heaters which had an open filament – my parents and grandfather lit their cigarettes using them. But to me Sissinghurst was the loveliest place on earth. There were no rules – we had such freedom there.

That Boxing Day, we had thrown a party for the neighbours. Afterwards, the snow started falling and we went to sleep praying that it would still be there in the morning. It was. The familiar landscape was made beautiful by snow and ice – even the statues were disguised.

We got dressed under the covers. I wore proper thick knickers with a vest tucked in, never out! Then we ran from our cottage into the garden. Sissinghurst’s White Garden, where only white and green colours were allowed, was an actual white garden with a Christmas-cake frosting. We found an old wooden loo seat in one of the outbuildings. Tying a rope around it, my brother and I squeezed ourselves into the seat and begged our father or one of the staff to whirl us around on the snowy lawn. The two lakes froze over, but we had no skates, so the surfaces were marked by our footsteps where we slithered about in our wellington boots.

Even the fountains at Trafalgar Square froze over. ‘We’re missing Dancing on Ice – get your skates on!’: family fun in Richmond park, Southwest London

By 27 December, every single county was affected by snow or ice. In parts of the South, depths of two and a half feet of snowfall were recorded. It was so cold that at Herne Bay in Kent you could walk a mile on ice from the beach into the sea.

The newspapers featured pictures of Stonehenge photographed from the air looking like sugar-covered biscuits. At Paignton Zoo in Devon, the keepers gave the elephants a warming tot of rum with breakfast. The RAC reported that cars were sliding off roads ‘like spinning tops’. And still the snow kept falling. The police took to wearing their pyjamas under their clothes. In London, a milkman started doing his round on skis. Later, when the freeze set in everywhere, people in Oxford could drive their cars across the frozen river to visit friends on the other side.

By the end of the year, the Tamar Bridge was the only link between Devon and Cornwall; every other road had closed. In Dorset, 71 passengers were trapped in two buses and had to spend the night in a café, where a month-old baby was given a cardboard box and blanket as a bed. Even Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s journey from his home in Sussex to London was fraught, his car and its police escort both had to be equipped with snow shovels. It got too cold to stay at Sissinghurst, especially for my pregnant mother, so we made the perilously icy journey back to London. We had to use a tractor to pull our car up the slope from the house to the main road so we could drive to the train station. We caught one of the last trains out of the village, which was packed as so many had been cancelled or derailed.

Ice cream, anyone? a London milkman makes his deliveries

Back in London, we lived at number 79, the ‘wrong end’ of the King’s Road. It was a bohemian mix of creative types and Labour politicians (the Conservatives lived at the posh end). Despite seven inches of snow with drifts of up to six feet covering the capital, London seemed to get back to something approaching functioning far quicker than the countryside. Pipes kept freezing and bursting, so we had no running water and had to queue in the cold, holding empty kettles and buckets to get water from the standpipe that had been erected at the end of our street. Remember that even in 1963, six million Britons shared a lavatory with others in their street – and many still washed in tin baths in front of the fire.

This was compounded by the sporadic walkouts by unions from power stations over hours and pay. The underground was plunged into darkness and in London’s hospitals, babies were born by candlelight. Yes, it seemed a bit desperate at times, but there was a feeling from everyone that you just got on with it. People still talked about the wartime spirit and ‘make do and mend’. If your place of work or school was open, you pulled on your wellies and off you went. Getting there became an adventure in itself.

We caught the bus to school every day alone, as children did then, and I can’t recall us ever not making it. We were fortunate to get to school without too much of a hindrance: all over the country, schools struggled to open. Eighty out of 86 British counties reported blocked roads. There were shortages of coal, food, oil and petrol although we were, then as now, warned against panic buying. Minister for Science Lord Hailsham held the weather personally responsible for the temporary loss of up to 200,000 jobs. Morale fell to a real low when even football matches had to be cancelled because of frozen pitches. As children, we found it a magical time, but for many it was one of hardship.

Juliet’s grandparents, novelist Vita Sackville-West and Sir Harold Nicolson, with their dog Rollo, Sissinghurst, 1960

At the weekends, my father would take us to the National Gallery, or on walks where familiar London sights were changed by the snow. At Trafalgar Square, the lions were cloaked in white coats and even Nelson at the top of his column had snow on his hat, while the fountain was frozen solid. The city looked otherworldly; the grey of winter transformed into a shimmering wonderland.

It felt new, crisp and clean. On your own street, there was no heavy machinery to clear the snow, so you went out with your dustpan and brush – or even a spoon – to clear a path. In the muffled quiet of the city, London rang to the sound of its resourceful inhabitants scraping doorways and paths with fireside shovels and dustpans.

Occasionally, we’d manage to persuade my father to make the journey to Sissinghurst, always thinking would-we-wouldn’t-we get there? In the countryside, there were snowball fights, snowman-building and skating, the ice creaking beneath our wellingtons. Skates were impossible to get hold of, shops having sold out when the freeze first hit. On one notable occasion, I was standing on my father’s feet as he walked on the lake when he lost his balance, tipping over and rendering me temporarily unconscious. Once I came round, he made me promise not to tell my mother.

In London, the capital’s ponds had long frozen over and become playgrounds for skaters. There’s a lovely story of a skating party the historian and earl Thomas Pakenham threw in St James’s Park, attended by his sister Antonia Fraser who was, like my mother, heavily pregnant so didn’t skate. He gave all his guests their own little lantern with a candle, and Antonia watched as they skated through the darkness, lighting the lake with their flickering flames, as the bongs of Big Ben sounded above them.

The thaw came on 6 March 1963 when, after more than 60 consecutive days of frost, Britain had its first frost-free night. We were ready for the thaw because it meant the birth of our little sister, who arrived as the first green shoots started breaking through. Even as a child I felt the sense that the coldness and darkness was over, and there was new life in the earth and in my mother’s arms.

Juliet aged eight, right, with brother Adam, five, and cousin Vanessa, 1963

* * *

I started researching and writing about this frozen winter before the pandemic. Now we are in another kind of paralysis.

These moments come when we are forced to re-evaluate. As I finished the book, the skies overhead where I live in East Sussex were clear of plane trails and the canals in Venice were running clear for the first time in years.

It is like an enforced pause, compelling us to stop and consider what really matters. As spring approaches, I feel hopeful.

Juliet’s latest book Frostquake is published by Vintage Publishing, price £18.99. To order a copy for £16.71 with free p&p until 14 February go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3308 9193

Source: Read Full Article