Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

SOCIETY

Knowing What We Know: The Transmission Of Knowledge From Ancient Wisdom To Modern Magic

Simon Winchester

William Collins, $34.99

Simon Winchester is a one-person encyclopaedia. His books are vast and, if you like granular detail, action packed. His COVID-lockdown project has been a history of knowing things, a multi-faceted account of the ways in which knowledge has been stored and retrieved, from the invention of writing to ChatGPT.

This is not a book that deals in any depth with epistemology, the philosophy of knowledge. It does not ask how we know what we know, that is, about the structure of knowledge. Nor does it deal with the neuroscience of knowledge: the role of those small parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus and amygdala, that do more for us than we commonly realise.

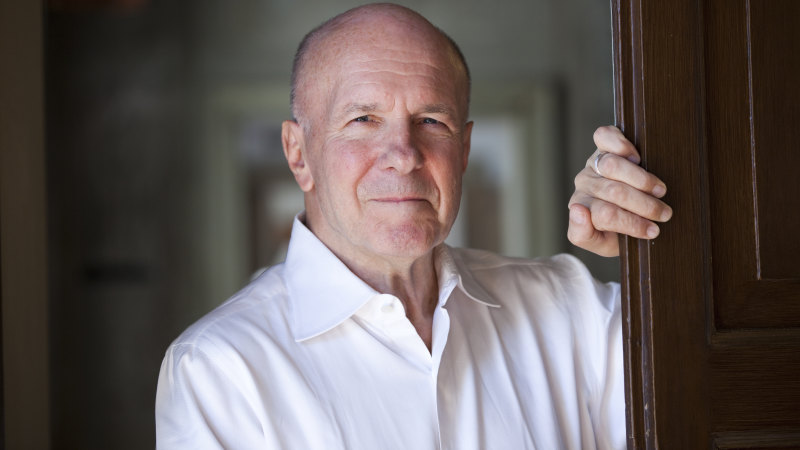

Simon Winchester is afraid that there will soon be no particular need to be intelligent at all.Credit: Loenardo Cendamo

Winchester is fascinated by libraries, museums, printing, education, examinations, dictionaries, newspapers, telegraphs and encyclopaedias. He is a vigorous and untiring guide to the people and places that created pervasive cultural entities that enabled the democratisation of knowledge while respecting such principles as objectivity, impartiality, and truthfulness. He is also a wide-eyed commentator on the steady process by which knowledge is being turned into plasticine, able to be moulded into any shape that suits an agenda. Winchester describes, for example, the manipulative campaign to encourage women to smoke in public.

Beneath all this he has a powerful question, more so because, while he has strong suspicions, he is not completely sure of the answer. He wonders if knowledge is becoming a thing of the past. His concern is based on the observation that nobody needs to know anything anymore. If you visit a doctor, they are likely to check your symptoms on their computer. The same applies to any kind of professional.

Credit:

So, what happens to us as a species if all our knowing is outsourced to machines. Is it possible to be wise, without personal knowledge. Winchester doubts it. But it is possible to be foolish or even nasty.

Winchester shares a story from his personal experience. In 1972, he was present as a journalist during the Bloody Sunday massacre in Londonderry. Lord Widgery’s subsequent sham investigation exonerated the British paratroopers.

After the truth emerged, some decades later, Winchester received a letter from a 96-year-old woman, the widow of his family doctor. Here he discovered that his late grandmother had been “abused, spat at, shouted and sworn at”. She had been monstered in the streets of her quiet town in south-west England because her grandson, an eyewitness, had dared to call out the behaviour of the troops who fired on an innocent crowd.

This is a powerful story, instantly recognisable in a world where anger and hysteria increasingly pass as knowledge. The underlying agenda of Knowing What We Know is illustrated by it. Of course, all the museums and encyclopaedias of history have cultural biases. They may contain errors. But they result from a far more painstaking process than has usually had a regard for objective truth.

The historical episodes recorded in this book are gorgeous in their detail. There are many of them, often told against the belief that knowledge comes easy. For example, Winchester describes the extraordinary Chinese examination process, the Gaokao, which, for a successful few, opens the door to an alluring position at university or in public service. It was suppressed by Mao and restored by Deng Xiaoping. It is ruthlessly democratic and embodies traditional Confucian values. “Knowledge makes humble. Ignorance makes proud.”

The preparation is exhaustive: months of cramming and grinding study. Then candidates come up against a question such as this: “The containers for milk are always square boxes, containers for mineral water always round bottle, and round wine bottles are usually placed in square boxes. Write an essay on the subtle philosophy of the round and the square.“

This question requires a nimble and creative mind. It also requires a mind that has learned humility through knowledge.

There is an array of vibrant characters in this book. One of them is Mau Piailug, from the Caroline islands, who had a legendary ability to navigate the Pacific by watching waves, listening to the ocean, and observing birds. Winchester asks us to consider the difference between his work and the use of a GPS.

“There will very soon be no particular need to be intelligent at all,” writes Winchester. “No need to be thoughtful. No need to think. Machines will do it for us. Or, to state once again the most nagging concern, machines may before long do it for themselves.”

Most of us will have wondered about these issues. Winchester does a fine job of helping us realise what we stand to lose.

Michael McGirr’s latest book is Ideas to Save Your Life (Text).

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article