In his novel Flaubert’s Parrot, Julian Barnes writes “what novelist, given the choice, wouldn’t prefer you to reread one of his novels rather than read his biography?“

Were he alive today, Philip Roth would probably agree with the English writer, even though he vetted Blake Bailey as his biographer and granted him access to everything, “no matter how intimate”.

“I don’t want you to rehabilitate me,” he told Bailey. “Just make me interesting.” With a life like Roth’s – 31 books, many of them brilliant, some controversial, two dramatic and failed marriages, umpteen affairs and an obsession with sex – it was hard to see how he could fail.

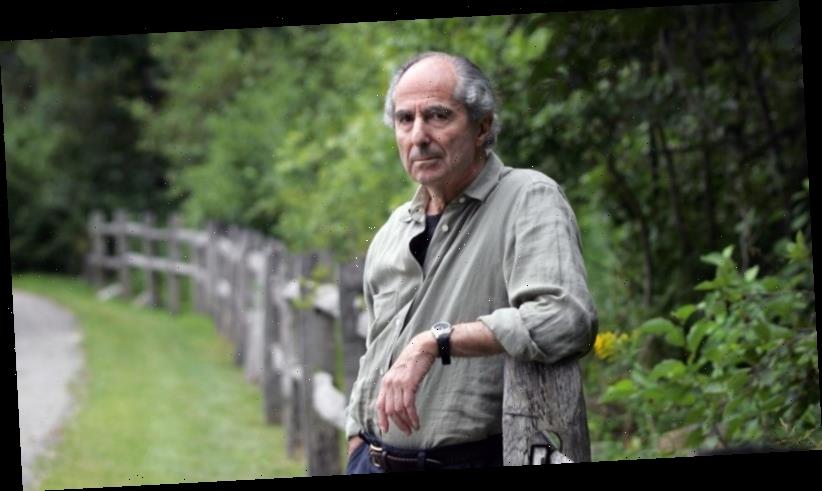

Philip Roth chose Blake Bailey as his biographer and vetted him thoroughly.Credit:Sara Krulwich

Philip Roth: The Biography is more than 900 pages long. It was published in the US and Britain this week but is not available in Australia until June 16. (There is no local print run and 1800 copies are being shipped here.)

American novelist Cynthia Ozick has described it in The New York Times as “a narrative masterwork both of wholeness and particularity, of crises wedded to character, of character erupting into insight, insight into desire, and desire into destiny. Roth was never to be a mute inglorious Milton.”

Philip Roth: The Biography by Blake Bailey.Credit:AP

Early on in the book, Bailey, author of lives of John Cheever and Richard Yates among others, points out that Roth’s “greatest urge was always to serve his own genius – amid the keen distractions, albeit, of an ardently carnal nature”. And it is that carnal nature – a nature that won’t come as a surprise to anyone who has read Roth – and its expression as related by Bailey that has successfully revived that hoary old chestnut: should we read books by those we think are flawed or worse authors (mostly men, with a nod to J.K. Rowling). Will so-called cancel culture cancel Roth?

Roth’s name has been mud in various circles since the beginning of his career. The Jewish community of New Jersey loathed his early works and his first big success, Portnoy’s Complaint, his masturbatory masterpiece. New York magazine conducted a survey among writers as to whether Roth should be considered a misogynist – the magazine once pictured him on its cover with a coverline declaring him to be one – and he was frequently bracketed with Mailer, Bellow and Updike and derided by feminist critics.

We live now in very different times. The MeToo movement has brought many necessary changes in how we conduct ourselves in life and in art. Certainly there are stories in Bailey’s book that could well make any reader think of Roth in a new light, although many of them have already appeared in his books, or in other books about him, including Claire Bloom’s memoir of their marriage, Leaving a Doll’s House. (Roth wrote a response that was never published, but is used by Bailey in the biography.)

Should we really care? And whatever your opinion, does it mean that masterpieces such as Portnoy, American Pastoral or The Plot Against America should be consigned to the literary dustbin? Should we turn our back on the late works such as Exit Ghost or The Dying Animal? Much of Roth’s writing is wonderful, moving and funny. The answer is surely no. He should still be read but you need to keep your thinking caps on. After all, nothing is really black and white.

As the British writer Rebecca West once said: “Just how difficult it is to write biography can be reckoned by anybody who sits down and considers just how many people know the truth about his or her love affairs.“

The British novelist David Baddiel, also Jewish and a comedian, writing in The Spectator, reckons that “the charge of how Roth treated, and depicted, women, however, is more threatening to his legacy, not least because he is a Jew, and not a woman, but more because maleness, along with whiteness, is where the cultural spotlight is presently being thrust away from”.

And he concludes that Roth’s literary confederates “wrote unjudgmentally. They were not, like so many novelists now are, trying to teach the reader, and Roth is the most un-didactic of all. His interest was not in the moral life, but just in life, lived, and then examined microscopically.”

Laura Marsh, writing in The New Republic, wouldn’t have a bar of that view. She says “possibly the worst thing you could do for Roth’s reputation would be to defend him on his own terms. His emphasis on settling scores with ex-wives and lovers draws attention to his signal failures of imagination — his lack of interest in the inner lives of women, his limited ability to reconcile his own experiences of pain with the co-existence of others’ suffering.”

And novelist Dara Horn had a similar view, writing in The New York Times under the headline “What Philip Roth Didn’t Know About Women Could Fill a Book” shortly after Roth’s death “in our current American culture, literature means little; the shared humanity that great literature inspires matters even less. What endures, sadly, is Roth’s lack of imagination, the unempathetic and incurious caricaturing of others that he turned into a virtue — and which now defines much of American public life.”

But Frank Furedi, writing in Spiked, identifies in Roth the exact opposite to Marsh – “it is important to read Roth rather than put him in front of a political tribunal. His work is the product of a powerful literary imagination that often forces one to look in directions one would rather avoid.″

Of course, plenty of writers have proven to be flawed geniuses. Dickens was abominable to his wife Catherine, so should we therefore not read Bleak House or any of his other magnificent novels? Graham Greene was demolished in Michael Shelden’s biography but remains the author of deeply humane fiction. Roald Dahl sounds like a dreadful man, but wrote wonderful books for children. Like Dahl, Patricia Highsmith was an antiSemite, while Rowling has been castigated for her views on trans people and for some that rules out the considerable joys of the Harry Potter books.

For once, Oscar Wilde was wrong. In his essay collection Intentions (1891) the great Irish writer wrote every great man has his disciples, “and it is always Judas who writes the biography”. Bailey is no Judas, but whether Roth loses readers remains to be seen.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article