Written by Zoe Beaty

Where are we in the ambition cycle right now? Stylist checks the pulse of working women.

“My ambition has always been very fiery,” says Georgie*, 30, from south London. Her 20s were spent fuelling this fire, chasing other-worldly jobs and foreign experiences. “I had so much energy to jump between careers,” she continues.

“For instance, my grad scheme was in qualitative research, then I went to work in farming and fishing in South America. I always had this real hunger to really immerse myself in whatever I found interesting and climb as high as possible in that field.”

On her return from South America in 2017, she spent two years working for a professional services firm. It was there that Georgie’s “soul crumbled a bit” – she was working all hours, not only investing her time but a lot of emotional energy into the job too. “It was futile,” she says, “I wasn’t earning enough to justify the level of commitment the firm expected.”

During the pandemic, she experienced a moment of clarity. She quit to work for herself in the creative industries, setting up a small agency with two other women to share the load of a start-up between them. They don’t work Monday mornings or Fridays and they prioritise balance over big budgets. “Now, I’d describe my ambition as little more than a flickering ember,” she says. “And I feel free.”

The cumulative effects of a pandemic and a growing cost of living crisis means that, like Georgie, many of us are finding ourselves at a pivotal crossroads when it comes to ambition.

Following the beginning of the so-called Great Resignation – an ongoing economic trend that, since 2021, has seen workers quit their day jobs en masse – terms such as “ambition burnout” and “career ambivalence” have become buzzwords. One American survey found that 45% of women describe themselves as “very ambitious”, down from 54% the year before. Meanwhile, The Cut hailed “mediocrity” king and Sarah Jaffe’s book Work Won’t Love You Back explored the damaging labour-of-love trap. For a while, it felt like we were all considering jumping off the career ladder.

That said, as we brace for the worst cost of living crisis in 60 years, many of us no longer have the luxury of abandoning ambition. Stylist’s own recent poll on reader ambition revealed that while 48% of respondents believe work “has its place, but it’s not [their] whole life”, 51% agreed they would like to feel more driven. Unsurprisingly, for 42% of those polled, increasing earnings was the main motivator. Chasing a dream job with a fancy title but sad salary is no longer aspirational; gone are the days of the #GirlBoss, and the hollow promise of changing capitalism. “There’s still a desire to redesign what work looks like,” Georgie says, “but it’s not all humblebragging and [being] power-hungry now. It’s about designing a happy life that includes work.” Now, we’re working hard because we have

For most, a sense of ambition is implanted in us early: for millennials, like me and Georgie, the sanguine thrum of Tony Blair’s hymn sheet – “education, education, education” – wherein the ambition to grow a generation of middle-managers is ever-ringing; for earlier generations, it was Margaret Thatcher’s hollow claim for that “no matter what your background, you have the ability to climb to the top”. Entrepreneurship and the idea of steering your own ship has grasped younger generations, with 76% of Gen Z telling one Monster survey that they see themselves as drivers of their own professional advancement and 49% are seeking to run their own business. We’re all so hyper-aware of what it means to succeed and what that looks like to each generation – but now, we’re starting to ask the right questions and, like Leanne*, 29, who works as a marketing executive, we refuse to accept there’s only one way.

“There was a point when I realised I wanted to stop scrambling to crawl up the career ladder,” says Leanne. “It was the day that my boss at a firm I’d worked relentlessly for refused to listen to where my strengths really lay and told me that my job was changing – getting more difficult, essentially, for no extra money. For years, I would have just accepted that this was my only option. This time, however, I decided I wanted out.”

Leanne had already found herself in a period of contemplation leading up to this moment: slowing down and working from home during the pandemic had “brought up a lot, in terms of emotions”, she explains. “It was stuff I would have just ignored in the past. I thought we were all going through life working hard, trying to climb the ladder, running on the treadmill. When we slowed down, it gave me the chance to reassess how I was spending my time, and I quickly realised that I wasn’t 100% happy in the life I was living – not even close.”

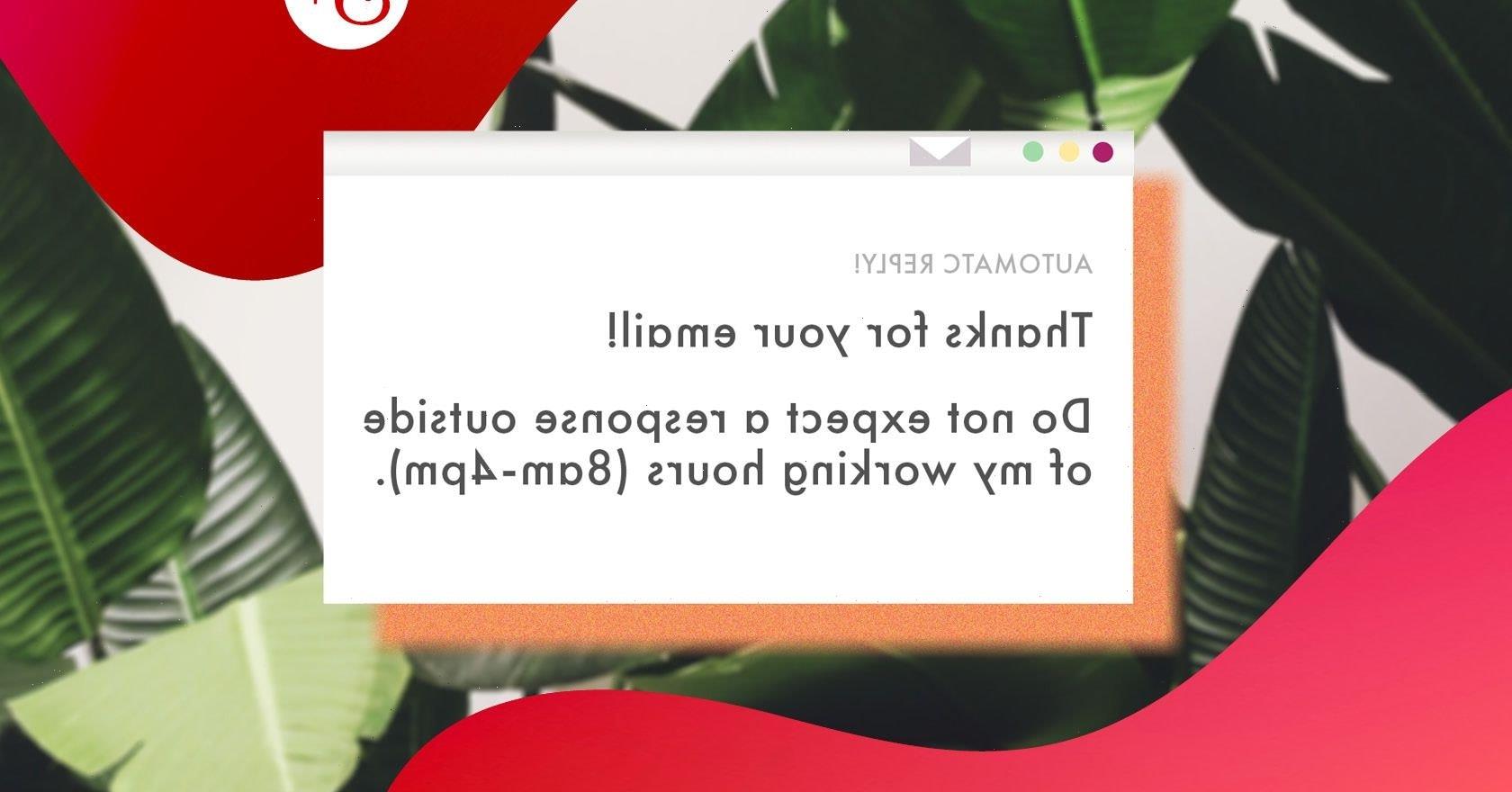

She trained as a yoga instructor, started teaching and quit her job – but decided not to risk doing that full time. Instead, she found another full time job in marketing and negotiated clear boundaries in her new role. “I wanted to expand

“I decided that I was going to set really strong terms. I would only work my set hours, for instance – I’ve not worked one minute of overtime – and if they don’t like that, it’s on them. They can get rid of me if they want, because I’ve still got another two streams of income – I do some travel writing on the side, too. Often, when work isn’t busy, I do my side projects in those hours to maximise my pay for that day and utilise the inevitable downtime between projects.

“I still have a lot of ambition, but I’m not putting all my bets on one, all-consuming job now, and I’m so much happier.”

Leanne’s mindset all comes back to “the biopsychosocial cycle”, Dr Audrey Tang, a chartered psychologist with the British Psychological Society, tells me. It’s a simple idea – this model posits that three major factors affect our thoughts, reactions and behaviours. Our biological make-up – our genes, the things that our families passed down to us – works in tandem with our psychological make-up (thoughts, emotions and feelings) and external socioeconomic or cultural factors.

Essentially, we’re not all born ambitious (biological), but we could easily become ambitious depending on how our psychology forms as we grow and move with the world or due to external environmental factors. Of course, it could also work the other way around. And, after the last few years, it’s not surprising to see that external, socioeconomic factors have had a sweeping effect on the majority of us, no matter what our genetic or learned attitude to success might have been previously.

Dr Tang feels that when it comes to ambition, our positions in the cycle might be split into two main groups. We all react differently to adversity (social) because of our biological make-up – so while one person might find that their ambitions increase in response to adverse conditions, another might feel the will to completely disappear.

“There’s an old piece of evidenced resilience research that says adversity can create the conditions in you to thrive, which you may not have had before,” Tang explains. “It’s down to the locus of control – this is a scale that determines how much you believe you’re in control of your life and how much of your life is controlled by something else, like fate or destiny. Those with a higher internal locus of control are more likely to be those who have recently pivoted and tried to take back more control at work or really assessed their values. Those people could be at the start of creating something for themselves at this point in the cycle. When things fall apart, some people instinctively step into gear to try and combat that.” And this is true even in the workplace.

“I still have a lot of ambition, but I’m not putting all my bets on one, all-consuming job now, and I’m so much happier”

Sandy, 38, is an example of this. Last year she quit her 17-year career as a nurse to escape the “insane and no longer palatable demand on every fibre of [her] being” to move into health and nutrition for a hugely “increased future earning capacity”. Annie, 35, also quit her job for the sake of her mental health at the end of 2020 and is now working freelance while she looks for something permanent. “My main motivation right now is a good salary and a job that I can create some emotional space from,” she says. “I am totally unwilling to make my job my ‘whole’ life again. In the longer term, I want to reach a point where I can work three or four days a week for peace of mind, paying bills, etc and then have the mental space to work on passion projects. My career ambition has gone out the window in the last two years, and I feel surprisingly free.”

The thing is, we’re all facing economic adversity that really is out of our control. So, while some of us might be compelled to look for work-based solutions, the remainder could be at a different point in the ambition cycle entirely. This is really just dependent on the individual. “There will be some people who are busy firefighting,” Dr Tang continues, “and not seeing anything from it. They are at risk of becoming increasingly depressed. You can quickly become too exhausted to have any form of drive or motivation.”

Other factors that might affect our ambition levels at times like these, Tang says, are parental scripts – the psychology developed from your childhood, like the difference in mindset if you were a first or third born or how embedded our desire for recognition and achievement is. The trick is to assess and listen closely to our values, whatever they are, and reaffirm them as much as possible in our daily lives. “Try to create a life for yourself that you don’t have to recover from,” Dr Tang says.

That’s exactly what Georgie is currently working on. She now lives in Portugal and helps run her young PR firm remotely. “We run our business equally between three founders – much less pressure than starting out alone – and still work really hard, but we’re finding ways to make sure that’s not the sole use of the majority of our time. The ultimate aim is to work as few hours as possible for maximum income. I suppose that’s the same for everyone, but the difference for me right now is that my identity is no longer entangled in my work. If this business fails, it fails. I’ll reassess and start again. I can’t live the way I used to anymore. I wasn’t happy. What’s the point?”

Georgie’s position is a privileged one but representative of what many of us are now aiming for. Whereas a decade ago, success appeared to be defined by hours spent in front of our screens, humblebragging about not having the time to take a lunch break, now it seems the ultimate flex isn’t being a high-flyer, but just… happy.

During another period of transition, as the world scrambles to adjust to rising costs, the losses we’ve already suffered during the pandemic and another war, it seems that our ambitions are transitioning too. “Honestly, changing the way I see ambition has brought me so much more contentment,” adds Georgie. “It’s overwhelming now to think about ‘climbing the ladder’ for the sake of status. Now I think: ‘How can I nourish everything I’ve got going on outside of my job?’ That’s ambitious, too, isn’t it?”

*Some names have been changed

Images credits: Getty

Source: Read Full Article