For our free coronavirus pandemic coverage, learn more here.

Insisting people get vaccinated in exchange for jobs or services risks entrenching disadvantage, with some experts warning it should not be a long-term feature of Australia’s COVID-normal future.

Victoria’s road map out of lockdown promises a range of freedoms for the fully vaccinated when Melbourne reopens, such as dining indoors or outdoors, going to weddings and funerals or getting a haircut, to be facilitated by a soon-to-be-rolled-out vaccine passport system.

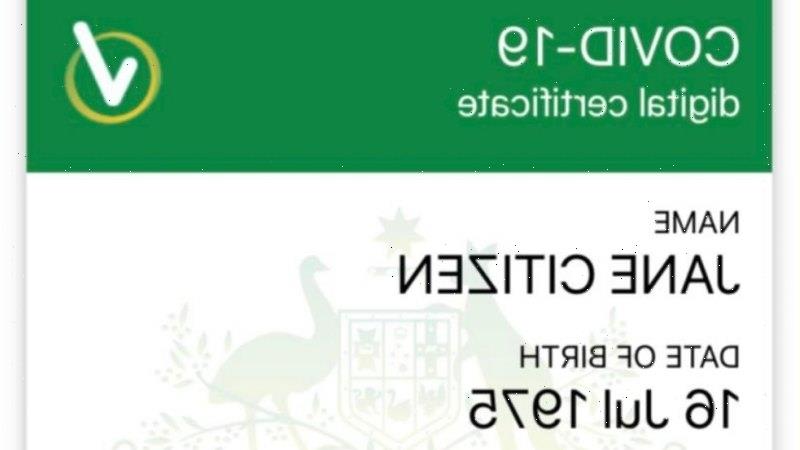

Vaccine passports are coming to Victoria.Credit:Fairfax

But as the state edges closer towards its goal for at least 70 per cent of eligible Victorians to doubled-dosed by late October, questions have emerged over the ethics, effectiveness and legality of mandates and passports.

NSW announced on Monday that it would allow unvaccinated people the same freedoms as the fully vaccinated on December 1 when about 90 per cent of the state’s adult population is expected to be vaccinated against COVID-19. That will will mean unlimited visitors in homes, unlimited gatherings outdoors, and retail and hospitality back to normal subject to a one person per two square metre cap.

Asked if Victoria would do the same, Premier Daniel Andrews said the government had not yet considered abandoning vaccine passports when the state hits certain vaccination thresholds.

The government has supported vaccine passports in order to facilitate the safe reopening of the economy, and society more broadly. Businesses in regional Victoria will begin a series of “vaccinated economy” trials from October 11, triggering greater freedoms for only fully vaccinated people for services such as hospitality and hairdressing.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews provides a coronavirus update on Monday.Credit:Scott McNaughton

“I wouldn’t want to give anyone a reason to wait five or six weeks [for greater freedoms for unvaccinated people], because I don’t think that’s a certainty,” Mr Andrews said on Monday.

“I’m not going to be saying to people ‘Oh, just wait five weeks and you’ll be able to have all the freedoms’. No, that’s not a guarantee at all here. We have not made that decision.”

Research by Torrens University shows that Melbourne’s immunisation rates are strongly tied to levels of socio-economic disadvantage.

John Glover, director of the university’s public health information development unit, said because of that a vaccine passport scheme would likely discriminate against “Indigenous Australians, refugees and a broad range of disadvantaged people”.

Human Rights Law Centre executive director Hugh de Kretser said that requiring people to be fully vaccinated in exchange for work or to access goods and services carried a range of human rights risks by restricting certain freedoms.

The issue, however, was whether these restrictions were “reasonable and justified.”

He said it was possible that mandatory jabs and the notion of a vaccine passport system could lead to legal challenges, but added “courts generally give a lot of discretion when there’s a public health emergency”.

Mandates issued by the Chief Health Officer, therefore, would be more difficult to challenge than those imposed by workplaces or hospitality venues.

“It’s possible that someone might want to challenge the public health order, but it would be very hard to be successfully challenged,” he said.

“In a workplace setting, if someone refused to get the vaccine and the employee issued disciplinary proceedings against them, you’d have to look at the reasons why someone didn’t want to get it, the context of their employment, and whether there were other less restrictive means available to accommodate their decision.”

A paper by the Collaboration on Social Science and Immunisation, a group of leading immunisation policy experts, published in the Medical Journal of Australia earlier this month suggested mandatory vaccination might be justified so long as people had plenty of opportunity to get vaccinated, among other conditions.

That had “absolutely not” happened, said Julie Leask, a leading immunisation policy expert at the University of Sydney and a co-author of the paper.

Sydney University vaccine expert Professor Julie Leask.Credit:Louise Kennerley

“Go to a country town that has limited access to GPs. You’ve got towns where Pfizer hasn’t been easily available,” she said.

Professor Leask warned that mandates should only ever be a last resort, noting that they “can widen the difference between the haves and the have-nots”.

“The key question for government is how long they can sustain a situation where the 10 per cent of the unvaccinated population in the state are unable to take part in social and cultural life,” she said.

“Because you will always have a group of people who will not vaccinate no matter what, no matter what hardship you throw at them”.

Dr Cassandra Goldie, chief executive of the Australian Council of Social Service, said Indigenous Australians, people living with a disability and people with insecure incomes all had lower vaccination rates.

“We face the very real prospect that the serious health risks faced by those still exposed to COVID will also now be compounded by new economic and social barriers. This will restrict people from job opportunities, as well as the mental health benefits of being able to socially connect with others,” she said.

“As a country, we must face the fact that we have not done enough yet to secure safe vaccination rates for people most at risk to ensure no one is left behind in our vaccination effort.”

Debate over vaccine mandates intensified last week amid protests involving workers, right-wing extremists and anti-vaccination activists at landmarks such as the West Gate Bridge and the Shrine of Remembrance after COVID-19 vaccines were made mandatory in the construction industry.

Federal Health Department immunisation guidelines specify that vaccines must be administered with “valid consent” – and for this consent to be legal, “it must be given voluntarily in the absence of undue pressure, coercion or manipulation”.

The issue is likely to prove politically contentious for the Andrews government when Parliament sits next week, with crossbencher David Limbrick’s libertarian Liberal Democrats planning a motion demanding the government publicly release any human rights assessment that it undertook in shaping its policies.

The motion would be put forward in the upper house, where Labor does not have a majority. Its success would depend on opposition and cross bench support.

Mr Limbrick, whose party opposes lockdowns, said “this is a very disturbing precedent for our state to be setting.

“What they’re setting up is a road map to a segregated society. Some people will be left behind.”

Dr de Kretser said the Human Rights Law Centre believed the public had a right to know what considerations had been made to ensure human rights were appropriately balanced.

Evidence suggests vaccines substantially decrease the risk of passing on the Delta strain of COVID-19, mostly by protecting people from catching the virus in the first place.

Vaccines from AstraZeneca and Pfizer are between 67 and 80 per cent effective at preventing infection with the Delta variant of COVID-19, UK data shows.

However, there are questions about how necessary protecting the vaccinated from the unvaccinated may prove to be.

Of the that smaller group of vaccinated people who do catch the virus, evidence suggests their viral load – how much virus they build up in their nose and throat, generally a good measure of how infectious they are – is as high as someone who is not vaccinated, although it seems to fall faster.

Associate Professor James Trauer, head of the epidemiological modelling unit at Monash University, said “it reduces your chances of catching and passing on the virus considerably, including for Delta”.

A vaccinated person faces “very little” risk from someone who is unvaccinated unless they are immunocomprimised, said Professor Tony Cunningham, director of the Centre for Virus Research at the University of Sydney.

“You may still get infected, but you’re not going to get severely ill”. The dificulty is that a person “could take this home (and infect) a vulnerable person”.

Stay across the most crucial developments related to the pandemic with the Coronavirus Update. Sign up for the weekly newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article