Earlier this week at Windsor Castle, Tom Cruise co-hosted the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee celebration. On Wednesday, he will appear at the Cannes Film Festival. On Thursday, he’ll be back in Britain for the Royal Film Performance, with the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.

All of these happenings are part of the promotional push for Top Gun: Maverick – a brilliant, if brazenly unpunctual sequel to the jamboree of jets and pecs that originally secured Cruise’s greatness in the mid-1980s. The PR strategy for this £120 million ($212 million) blockbuster is clear: aim the lead actor’s signature grin at the entire world, and blast away. Tooth-flashing tirelessness has long been integral to the Cruise brand. But this time, his publicity schedule has the air of a last-ditch plea for the idea of the movie star itself.

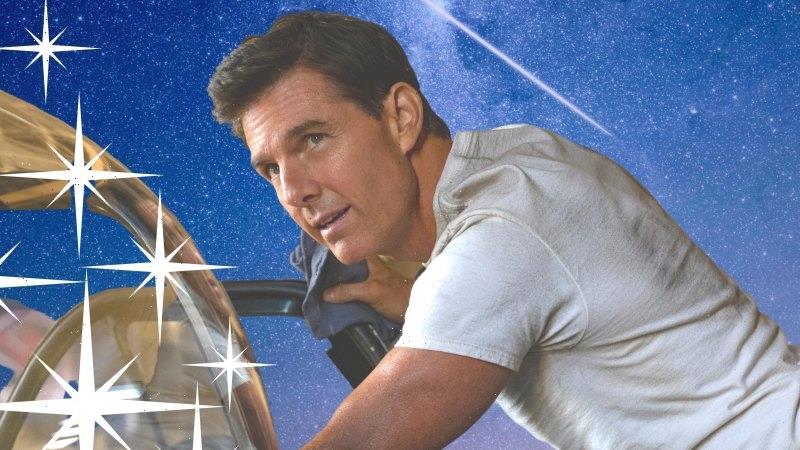

Top Gun: Maverick pistons along on Tom Cruise’s magnetism, and dazzles you with old-fashioned idolisation.Credit:Scott Garfield/AP

The concept has been with us for almost as long as popular cinema has: as early as 1908, the New York-based Biograph Company was bombarded with letters from fans demanding they identify the regular leading lady of their popular D. W. Griffith shorts, then known publicly only as the Biograph Girl. Her name, Florence Lawrence, had been deliberately withheld by the studio, who feared a public profile would afford her greater artistic leverage and salary claims.

Full marks for prescience. Nine decades later, performers such as Julia Roberts and Jim Carrey could command $20 million up front for a single, original film, the very existence of which hinged on their willingness to make it.

Yet in today’s Hollywood, enthusiasm for the star vehicle, and indeed for stars per se, seems at an all-time low. In the age of the franchise, it’s characters and worlds that sell, not actors. Fans aren’t paying to see Robert Downey Jr or Chris Evans – for evidence, just look at how their non-Marvel films usually fare – but Iron Man and Captain America themselves.

No wonder Bradley Cooper and Ben Affleck, two of Hollywood’s most prominent leading men, each recently suggested that cinema no longer holds the appeal it once did. (Not unrelatedly, both were talking after the commercial failure of adventurous big-budget projects, Nightmare Alley and The Last Duel.)

Meanwhile, Carrey now depends on Sonic the Hedgehog to draw a crowd, while Roberts’ most recent film (2018’s Ben Is Back, if you’re wondering) vanished from cinemas after a week – and the actress retreated to the small screen. What about the bright young hopes who have taken up their wildly lucrative mantles? Well, that’s part of the problem: Hollywood hasn’t managed to produce any.

Since the minting of the 1990s A-list – among them Roberts, Carrey, Will Smith, Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Meg Ryan and, of course, Cruise himself – the movie star has become a critically endangered species. Some of the reasons for this are cultural, others are technological, and most are unconnected. But the cumulative effect has been an earthquake.

Howard Bragman has kept a close eye on the fault lines. A PR executive who specialises in crisis management for high-profile individuals, he understands as well as anyone in Los Angeles the value and fragility of an actor’s public image. Talking on the phone while his dogs yap happily in the background, the 66-year-old agrees that Cruise may be the last of his breed.

“Tom still plays by the old rules. He’s a gentleman, a professional, and he works harder than anyone I know,” Bragman tells me. “He knows he can’t take it for granted that the fans will turn out, so works his arse off to ensure they do.”

This runs back to fault line number one: the sheer number of films now fighting for your attention. With cinema’s early-21st-century switch from celluloid to digital, movies suddenly became immeasurably easier to make and distribute, which meant there were considerably more to go around. In 2000, just under 400 films were released in UK cinemas; by 2019, that figure had more than doubled, to say nothing of the thousands available to stream at home, and new online platforms hatching stars of their own.

“It’s harder than ever for a young actor to get a toehold on the public consciousness because there’s so much new stuff coming at you,” says Bragman.

Then there’s fault line number two: the internet, and all the ways it can imperil a star’s reputation. It arrived as not just a new media frontier, but an entire weather system, where squalls blew up without warning, and painstakingly chiselled edifices could be instantly blown flat.

In 2006, after 14 years, Cruise parted ways with Paramount Pictures over the studio’s concerns about his conduct while promoting War of the Worlds. For one thing, there was the growing prominence of Scientology in his public pronouncements. Then came the bouncing on Oprah Winfrey’s settee. Thanks to the rise of gossip blogging, this eccentric TV moment became one of the first celebrity memes – a new threat on the media landscape that even the sharpest publicist couldn’t suppress.

Cruise in a scene from Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 erotic thriller, Eye Wide Shut.

Rebuilding his image in its aftermath took Cruise eight years, as well as a narrowing of artistic horizons. Those daring mid-career roles – the loathsome pick-up artist in Magnolia, the stewingly jealous husband in Eyes Wide Shut – were supplanted by various spins on Cruise’s own loveable dynamo public persona in a number of action-propelled crowd-pleasers.

“Even the stars of the Golden Age had ups and downs,” Bragman stresses. “Some of the biggest names in the world were written off and came back to prove others wrong.” The difference today, though, is that the writing-off itself – or “cancellation” – can become a story to rival anything Hollywood can concoct.

The term “cancel culture” started gaining currency in 2014. But it was with #MeToo three years later – in which the likes of Harvey Weinstein were held accountable for years of sexual predation – that the idea took hold that calling out misbehaviour online could be a swift and effective path to justice. Never mind that the big #MeToo scalps had all come from painstaking investigations by experienced print journalists. Social media had scented blood.

As a veteran of crisis PR, Bragman has handled many #MeToo-related cases, and has noticed a new readiness to leap to outrage. He recalls a recent example in which a woman felt violated by an actor after discovering the lines he’d used to charm her into bed had also been successfully used, word for word, on earlier conquests. Many of the lower-level #MeToo culprits were, he explains, “in the vernacular, schmucks. They may not have done the worst things, but their attitudes made them easy targets. Likeability is a very big issue right now.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find a studio willing to make 1995’s Clueless in today’s times.Credit:Paramount Pictures

The shift in romantic mores has also nobbled Hollywood’s most efficient machine for turning actors and actresses into public obsessions. Fault line three is the one that swallowed up romantic comedy in the early noughties, after almost a century of kindling mass desire and delight.

Rom-coms were where audiences could be seduced by proxy by the playboy and/or goddess of their choosing. But the genre’s lopsided power dynamics, manipulations, deceptions and frankness around sexual attraction all became ripe for reproof in our newly prudish age. Never mind the toxic likes of You’ve Got Mail, Groundhog Day or Pretty Woman with their deceitful menfolk. What studio these days would even consider making Clueless, from the Neolithic wastes of 1995, in which the lovers are step-siblings, and the girl is 16 years old?

The point of no return was 2003’s Love Actually, in which all the men were stalkers, pesterers and boors, and the women meek, pliant drips. From then on, mischief and chemistry dwindled, and romantic leads became vapid and desperate – the last people on earth the public would fall in love with.

The lovers also had to contend with the racket next door. Fault line four opened up in the late 1990s, when advances in digital visual effects meant directors’ palettes were no longer limited by what could be physically realised. Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace proved not only that worlds with no grounding in reality could be put on screen, but that they could also be peopled by characters who didn’t physically exist. Two years later, the first films in the Lord of the Rings trilogy and Harry Potter series opened in cinemas, and the age of the franchise truly began.

The Lord of the Rings franchise, along with Harry Potter, changed cinema forever.Credit:AP

In 2006, Disney dramatically restructured its business around this new normal. Its focus shifted almost exclusively to films that could bolster other businesses: toys, video games, TV spin-offs, theme-park rides. Disney’s acquisition of Marvel Entertainment at the end of 2009 showed how ruthlessly this strategy would be pursued. Digital excess rendered performance irrelevant: in the latest Doctor Strange, even a simple tactile pleasure such as watching Benedict Cumberbatch knotting his tie is deadened by CG.

Yet with Cruise, even in the franchise realm his personal presence feels non-negotiable. You can recast Batman whenever you like, but in the Mission: Impossible films, there can only be one Ethan Hunt.

If anyone can outrun these ruptures, it has to be the man who turned running into his signature move. Top Gun: Maverick pistons along on Cruise’s own magnetism – it’s easily the best action film since Mad Max: Fury Road, but it dazzles you with old-fashioned idolisation rather than carnage.

How has Cruise defied the quake? For Bragman, it’s a question of will. “You’re talking Tom,” he audibly shrugs. “He’s about to turn 60, and he gets the world is changing. But he’s able to keep doing it when nobody else can because he believes he still can. It’s kind of that simple.” The maverick isn’t coming in to land just yet.

Top Gun: Maverick is out on May 26.

The Telegraph, London

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article