TONY BLAIR: The world needs to agree a form of Covid passport – and Britain should lead the way

Lockdown is the weapon of choice of Governments around the world to reduce the spread of Covid-19, but let’s be clear – the effects on the nation’s health and economy are severe.

Jobs and livelihoods lost. A huge bill for future generations to pay. It means postponing the treatment of other conditions like heart disease and cancer; and a deterioration of mental health.

The reality, however, is that lockdown will stay until the vaccination programme reaches a large enough number of the population to give us some form of herd immunity.

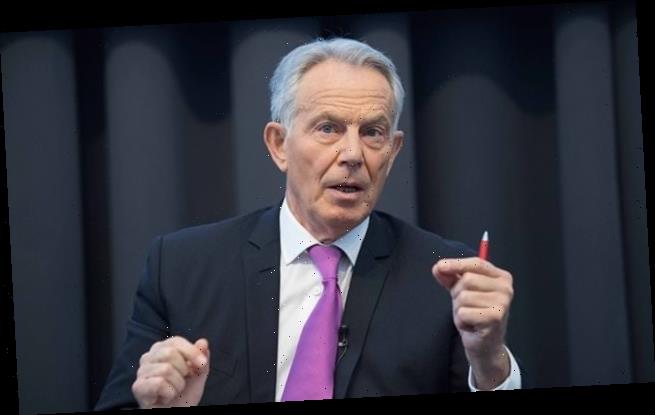

It is fortunate that Britain is in a good place relative to the rest of the world, says former Prime Minister Tony Blair (pictured)

The new variants of Covid-19, with greater transmission rates but not lower deadliness, combined with the alarming recognition that more variants could be on the way, have left us a horrible choice: mass vaccination or mass lockdown.

Globally, there is a vast scrambling to get vaccine. It is fortunate that Britain, with a well-executed plan to source vaccines, including our own Oxford/AstraZeneca jab, is in a good place relative to the rest of the world.

Even so, each week that passes before we can re-emerge to some form of ‘normal’ is a hammer blow.

What happens, though, when a majority of our population is vaccinated but other countries lag behind? How does the world return to at least some of the physical interaction we used to take for granted?

This is not just about holidays. It’s also about business travel and freight.

It’s about improving levels of confidence in going back to the workplace. Travelling on public transport. Joining events with large crowds. Most of all, seeing loved ones, especially those who may be among the most vulnerable to Covid-19.

With my team at the Institute for Global Change, I have looked at this from every angle and come to this conclusion: there is no prospect of a return to anything like normal without enabling people to show their Covid status, whether that means they have been vaccinated or recently tested.

And the good news is that technology allows us to make this work effectively and with privacy.

More than 120 countries, including our own, already demand that international travellers show proof of a full negative test result before entry. Once vaccinations become widespread, this demand will naturally move to vaccination.

Call it a passport, a certificate or proof of status – we will want to know.

We can’t stay in lockdown for ever. But we know from experience that as we come out of lockdown, the disease will start to spread again unless we keep some form of controls on who can come into our country and unless we take reasonable precautions to stamp on any outbreak should it recur.

This is not about discrimination, or hostility towards those not vaccinated or tested. It is a completely understandable desire to know whether those we mix with might be carrying the disease.

Have they had an internationally recognised test (based on PCR swabs, which look for traces of Covid’s genetic material, or other equally valid tests as they are developed) to demonstrate that they are free form the virus?

Have they been vaccinated and, if so, is that with one or two jabs?

It is increasingly obvious that other countries feel the same. There is already a host of initiatives starting around the world with this aim in mind.

My Institute for Global Change is involved in many of them, including the CommonPass initiative from the World Economic Forum. Individual countries such as Greece, which is conscious of the huge impact of Covid on its tourist industry, are calling for global agreement on the issue. The African Union has started its own preparations.

The airline and tourism industries are among those most anxious for such a passport. Tourism accounts for roughly ten per cent of the world economy. It employs millions the world over, including in Britain.

And that means a wide range of businesses are clinging on, effectively on government life-support – provided, that is, they’re lucky enough to be in countries where the government can just about afford to subsidise them.

But without clear light at the end of the tunnel, without confidence in the future, these businesses are going to collapse. Some already have.

Once it is plain that we need to know the status of someone in order to feel safe mixing with them, then certain other things must flow.

We need a system of verification that is simple, for example a QR code shown on a mobile. Or a valid paper certificate – one that minimises the possibility of fraud. We need something which is easily checked against an agreed set of standards.

It is not as if proof of vaccination is completely new. Many countries already require travellers to show such proof for yellow fever and other diseases.

What would be crazy is for the world to try operating with different standards, different means of verification, a patchwork, an unco-ordinated stack of competing systems. That would lead to chaos.

Governments will have to lead this. We cannot leave it up to GPs to issue paper certificates when they already have quite enough on their plate.

The sensible thing would be for the UK – which for 2021 has the lead in the G7 group of developed nations – to agree and help impose a common set of standards and rules in consultation with other countries and groups of nations. That would be in the interests of everyone.

But we should start work on it now so we’re ready to go by June when the G7 is held in Cornwall.

There is still so much we don’t know about Covid, and so much we will get to know thanks to our experience of mass vaccination. It seems likely, though, that those who are vaccinated are not merely less at risk from the disease but also transmit it less.

Early results from the AstraZeneca vaccine show a 67 per cent reduction in transmission after vaccination while data from Israel show only 0.04 per cent of those who had been vaccinated were then infected, none of them seriously.

We should also learn from our experience with testing. Early on, I became convinced that we should do mass testing, using rapid tests which could be done at scale even if they were admittedly less accurate than the gold standard PCR test.

When over half of those who get Covid suffer no symptoms but can still spread the virus, it always seemed odd to test only those with symptoms.

When Slovakia tested its whole population, using rapid tests, it discovered twice the number of cases as the previous official figures indicated.

The University of Illinois used mass testing on its campus to stay open through the pandemic.

In Liverpool, rapid tests picked up 70 per cent of those with high ‘viral loads’ (those who were heavily infected and might well have been passing it on) but who were nonetheless showing no symptoms.

Now – and with much better mass tests available – workplaces are being encouraged to use tests to reopen.

The point is this: people want to know that those with whom they come into contact are relatively safe – that they are less likely to give them the disease.

This will be the case not just with travel, but with our daily lives, too – with everything from going to work to visiting elderly relatives.

We have the technology which allows us to do this securely and effectively. The need is obvious. The world is moving in this direction.

We should plan for an agreed ‘passport’ now. The arguments against it really don’t add up.

lTony Blair is the founder and executive chairman of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

Source: Read Full Article